CHAPTER NINE

The Winds of Change

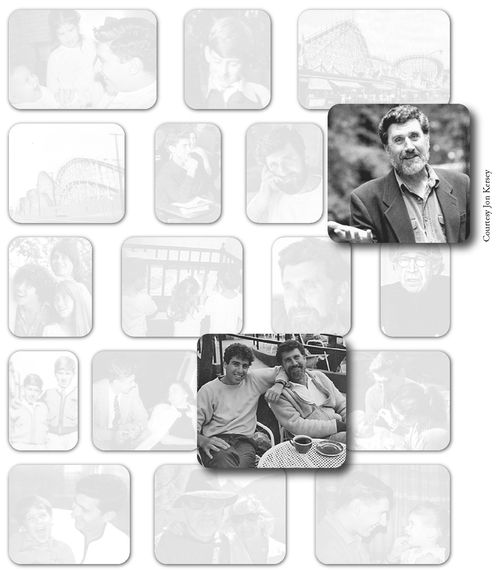

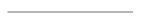

Lecturing, 1994 (top).

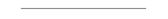

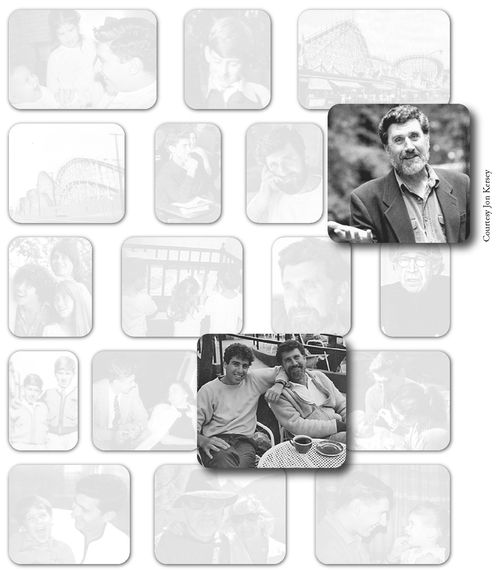

Budding social psychologist Josh and his first mentor at their favorite coffeehouse, 1989.

When we moved to Santa Cruz from Texas, I felt I was in paradise. The weather was heavenly. I was near an ocean again. And I was at a liberal institution with a liberal student body. As a place to live, Santa Cruz was everything Vera and I had hoped it would be for ourselves and our family, then and now; three of our four children still live in or near Santa Cruz. At the university the highs were higher than at any place I had ever taught; however, the lows were also lower.

During my first three years on campus, my office was next to a philosopher on one side and a physicist on the other; across the corridor was a historian, and two doors down, a poet. One result of this happy proximity was that the philosopher next door to me, Ellen Suckiel, and I developed a course we called Philosophical and Psychological Foundations of the Life Cycle that, year after year, received the highest student evaluations on campus. In practice the college system at UCSC was a wonderful way to teach undergraduates because it combined the best aspects of a small private college, like Swarthmore or Reed, with the facilities of a large state university. Hal blossomed there; his excitement (and mine) inspired Neal, Julie, and Josh to follow him to UCSC.

Initially, the living-learning community at Kresge College worked beautifully. As in all of the colleges, students could take standard university courses in traditional subjects, such as history, psychology, or biology, as well as special interdisciplinary seminars. At Kresge the seminars added a level of intensity to the usual academic discussion, because they were often run as T-groups. The students were required to learn the course material, and professors retained their authority to make intellectual demands, set requirements, and evaluate the students’ performance. But students also learned about themselves, their relationship to their peers, and ways to communicate clearly and effectively. The T-groups I had been conducting in Bethel, Maine, had a finite duration, about two weeks, and when they were over, participants dispersed to their home cities—Boston, New York, Chicago, Montreal—saying fond good-byes to their groupmates and taking whatever they had learned back home. At Kresge, however, participants remained right there. The result was the emergence of a close-knit community where the traditional academic barrier between “living” and “learning” was obliterated.

In 1970 Carl Rogers, the leading clinical psychologist of his time, had called the encounter group “the single most important social invention of the 20th century.” Yet this great social invention flourished for only about two decades. The T-group was doomed by the return of the Puritan influence on our society—an influence entrenched in American culture, one that ebbs and flows but never quits. When I was at Harvard I had thought that Tim Leary and Dick Alpert’s glowing hope for the power of psilocybin to empty our prisons was naive, but I also found their optimism thrilling and contagious. I was excited by the decade of antiwar protests and movements for equality and the rosy future these events presaged. And I loved the work we were doing in encounter groups, promoting the notions that barriers between people could be lowered, that warmth and understanding could overcome suspicion and prejudice. My own naïveté rested on the assumption that progress toward these goals would be linear. “If things are this good now,” I thought, “just imagine how they will be in ten years!”

What I did not anticipate was that many people outside the college would come to view the goings-on at Kresge with suspicion, others with envy, and a good number with outright hostility. “Hey! Those people are having fun over there! If it’s that much fun, it can’t be educational!” Once, one of our students told a professor that he was headed over to Kresge for an appointment with Michael Kahn, and the professor said, in all seriousness, “Be careful—he might hug you.” It was easy to lampoon T-groups as being nests of touchy-feely self-absorption and pseudopsychology. The campus had a new chancellor and Kresge had a new provost; neither supported the living-learning experiment. The younger faculty members, sensing the opposition of the administration and wider community, were reluctant to participate. Thus, within three years of my arrival at Kresge, the living-learning community collapsed, a harbinger of the demise of T-groups across the country. The students were disappointed. I was heartbroken.

Lecturing, 1994 (top).

Budding social psychologist Josh and his first mentor at their favorite coffeehouse, 1989.

When we moved to Santa Cruz from Texas, I felt I was in paradise. The weather was heavenly. I was near an ocean again. And I was at a liberal institution with a liberal student body. As a place to live, Santa Cruz was everything Vera and I had hoped it would be for ourselves and our family, then and now; three of our four children still live in or near Santa Cruz. At the university the highs were higher than at any place I had ever taught; however, the lows were also lower.

During my first three years on campus, my office was next to a philosopher on one side and a physicist on the other; across the corridor was a historian, and two doors down, a poet. One result of this happy proximity was that the philosopher next door to me, Ellen Suckiel, and I developed a course we called Philosophical and Psychological Foundations of the Life Cycle that, year after year, received the highest student evaluations on campus. In practice the college system at UCSC was a wonderful way to teach undergraduates because it combined the best aspects of a small private college, like Swarthmore or Reed, with the facilities of a large state university. Hal blossomed there; his excitement (and mine) inspired Neal, Julie, and Josh to follow him to UCSC.

Initially, the living-learning community at Kresge College worked beautifully. As in all of the colleges, students could take standard university courses in traditional subjects, such as history, psychology, or biology, as well as special interdisciplinary seminars. At Kresge the seminars added a level of intensity to the usual academic discussion, because they were often run as T-groups. The students were required to learn the course material, and professors retained their authority to make intellectual demands, set requirements, and evaluate the students’ performance. But students also learned about themselves, their relationship to their peers, and ways to communicate clearly and effectively. The T-groups I had been conducting in Bethel, Maine, had a finite duration, about two weeks, and when they were over, participants dispersed to their home cities—Boston, New York, Chicago, Montreal—saying fond good-byes to their groupmates and taking whatever they had learned back home. At Kresge, however, participants remained right there. The result was the emergence of a close-knit community where the traditional academic barrier between “living” and “learning” was obliterated.

In 1970 Carl Rogers, the leading clinical psychologist of his time, had called the encounter group “the single most important social invention of the 20th century.” Yet this great social invention flourished for only about two decades. The T-group was doomed by the return of the Puritan influence on our society—an influence entrenched in American culture, one that ebbs and flows but never quits. When I was at Harvard I had thought that Tim Leary and Dick Alpert’s glowing hope for the power of psilocybin to empty our prisons was naive, but I also found their optimism thrilling and contagious. I was excited by the decade of antiwar protests and movements for equality and the rosy future these events presaged. And I loved the work we were doing in encounter groups, promoting the notions that barriers between people could be lowered, that warmth and understanding could overcome suspicion and prejudice. My own naïveté rested on the assumption that progress toward these goals would be linear. “If things are this good now,” I thought, “just imagine how they will be in ten years!”

What I did not anticipate was that many people outside the college would come to view the goings-on at Kresge with suspicion, others with envy, and a good number with outright hostility. “Hey! Those people are having fun over there! If it’s that much fun, it can’t be educational!” Once, one of our students told a professor that he was headed over to Kresge for an appointment with Michael Kahn, and the professor said, in all seriousness, “Be careful—he might hug you.” It was easy to lampoon T-groups as being nests of touchy-feely self-absorption and pseudopsychology. The campus had a new chancellor and Kresge had a new provost; neither supported the living-learning experiment. The younger faculty members, sensing the opposition of the administration and wider community, were reluctant to participate. Thus, within three years of my arrival at Kresge, the living-learning community collapsed, a harbinger of the demise of T-groups across the country. The students were disappointed. I was heartbroken.

The Kresge experiment having failed, I moved to Adlai Stevenson College, one of the more traditional UCSC colleges, where I devoted most of my energy toward strengthening the graduate program in psychology. When I had first arrived there was no graduate program to speak of, and none of my colleagues in social psychology were actively engaged in experimental research. I urged the department to hire Tom Pettigrew and, later, Anthony Pratkanis, two superb social psychologists with active research agendas, and soon Tom, Anthony, and I had developed a graduate program in applied social psychology that was attracting good students. Yet the very factors that made our university a great environment for undergraduates militated against graduate training. Because the members of the Psychology Department were scattered in all corners of the campus, there was no way for graduate students to interact easily with us. After my experiences at Harvard, Minnesota, and Texas, where my graduate students were in offices adjacent to mine and we could interact freely and easily throughout the day, I felt that student-faculty proximity was crucial to a good graduate program. I convinced the chancellor to provide us with a trailer and place it on the edge of Stevenson College; the trailer provided space for experiments as well as offices for the graduate research assistants. Not luxurious, but neither was that attic at 9 Bow Street.

In 1977, against my better judgment, I agreed to serve as interim department chair until we could find someone to take the job on a permanent basis. That year, the graduate student colloquium committee decided to invite Arthur Jensen to give a talk to the psychology faculty and graduate students. Jensen was a controversial figure. His research on intelligence had led him to the conclusion that there was a genetic component to the average racial differences in IQ. This was, of course, volatile stuff, and coming as it did in the midst of the civil rights movement, it was inflammatory.

I had read one of Jensen’s key papers and was persuaded that he was a serious scholar and not a bigot. As a social psychologist, however, I thought Jensen was overlooking environmental and situational explanations for racial differences. I was reluctant to invite him to give a colloquium not because he was controversial but because, given our limited departmental budget, I would have preferred to invite psychologists who I thought were doing far more interesting research. But the graduate student committee argued that it would be exciting for them to have the opportunity to challenge Jensen’s conclusions in a face-to-face, friendly confrontation. As chair, I was not looking to foment controversy, nor was I looking to avoid it. I agreed to invite him.

On the phone Jensen accepted my invitation and then astonished me by demanding protection; he explained that, during the preceding few months at several universities, students had shouted him down, spat on him, and jostled him. I assured him that would not happen at Santa Cruz because we had an open-minded student body and, even more important, our colloquia had always consisted of small gatherings of about ten graduate students and seven or eight faculty members, sitting around a table in a seminar room. I joked that our graduate students hardly ever spat on our guests. Jensen was not amused.

Then, much to my surprise and disappointment, the night before his arrival, a few hundred students staged a rally at which they burned one of his books and some of his research publications and announced that they intended to storm the colloquium the next evening. In Texas I had become all too familiar with the intolerance of right-wingers, so it was a shock to encounter the intolerance of liberals—people whose values I shared but whose tactics could be just as undemocratic as those I had encountered in Austin.

The anger and potential violence of the students posed a dilemma for me. I had guaranteed Jensen safety; the prospect of two hundred students “storming” a seminar room that held twenty was alarming. Should I have the cops come out to protect him? Should I call off the meeting? Neither choice was acceptable. I did not want to create the conditions for a student-police confrontation, but neither did I want to capitulate to undemocratic rowdiness. After a good deal of thought, I arrived at what I considered to be a judicious solution: I decided to hold the seminar at a professor’s home and posted a notice on the seminar door announcing that the meeting had been moved off campus. When a horde of undergraduates arrived at the seminar room and found no one there, they were furious.

The next day I was vilified in the student newspaper, which called me a racist for inviting Jensen and a coward for not letting the students get at him. The irony was not lost on me. Ten years earlier, in Austin, I had been called a “nigger lover.” Now, in Santa Cruz, I found myself accused of being a racist. Indeed, in a bizarre echo of Austin, that night I received an unpleasant phone call at home. It was from an angry student rather than a gravelly voiced man, and it came at eight at night rather than two in the morning, but it was disquieting nonetheless.

“Are you going to be keeping your office hours in the patio outside the Kresge coffeehouse tomorrow, as usual?”

“Of course,” I responded.

He said, ominously, “You better be there.”

When I arrived at the patio and approached my usual table, there were three students waiting for me: Hal, Neal, and Julie Aronson. (Josh was still in high school.) Vera had told them about the phone call and the possibility of trouble, and they showed up to offer their dad moral support and, if needed, physical protection. Ten minutes later a few dozen students, some carrying torches and all chanting “Aronson’s a racist,” marched up the hill to the patio and surrounded my table. They activated a tape recorder and recited into the microphone a list of their grievances against me. Then they thrust the microphone in my face and said, “What do you have to say to that?”

I did what almost any liberal professor would have done: I gave them a five-minute lecture extolling the beauty of the First Amendment. I told them that I regretted shutting students out of Jensen’s talk, but the book burning and rowdiness of the previous evening had left me no choice. I told them that the point of education is not simply to confirm what we believe but to hear and discuss the ideas of serious scholars who hold a wide range of opinions—some of which we will disagree with, some of which we may even find offensive. At a university, learning often emerges from argument, but the argument must be civil. The students listened. A few even applauded. They dispersed quietly.

I looked over at my kids. They were grinning.

“Not bad, Dad,” said Hal.

“Very good,” said Julie.

“Let’s get some coffee,” said Neal.

It took me a while to overcome the distress I had felt, but I came to see the Jensen incident as reflecting a combination of student qualities that I cherish: being feisty and teachable. I’d never encountered that combination before, not even at Harvard. In the main, Harvard undergrads were more sophisticated and knowledgeable than UCSC students, but in my experience they also seemed more conventional. I admired and enjoyed the UCSC students’ willingness to speak their minds, ruffle feathers, and listen, and they repaid me by flocking to my introductory social psychology course. In 1979, when the Alumnae Association decided to establish an annual Distinguished Teaching Award, they honored me as their first recipient.

The Kresge experiment having failed, I moved to Adlai Stevenson College, one of the more traditional UCSC colleges, where I devoted most of my energy toward strengthening the graduate program in psychology. When I had first arrived there was no graduate program to speak of, and none of my colleagues in social psychology were actively engaged in experimental research. I urged the department to hire Tom Pettigrew and, later, Anthony Pratkanis, two superb social psychologists with active research agendas, and soon Tom, Anthony, and I had developed a graduate program in applied social psychology that was attracting good students. Yet the very factors that made our university a great environment for undergraduates militated against graduate training. Because the members of the Psychology Department were scattered in all corners of the campus, there was no way for graduate students to interact easily with us. After my experiences at Harvard, Minnesota, and Texas, where my graduate students were in offices adjacent to mine and we could interact freely and easily throughout the day, I felt that student-faculty proximity was crucial to a good graduate program. I convinced the chancellor to provide us with a trailer and place it on the edge of Stevenson College; the trailer provided space for experiments as well as offices for the graduate research assistants. Not luxurious, but neither was that attic at 9 Bow Street.

In 1977, against my better judgment, I agreed to serve as interim department chair until we could find someone to take the job on a permanent basis. That year, the graduate student colloquium committee decided to invite Arthur Jensen to give a talk to the psychology faculty and graduate students. Jensen was a controversial figure. His research on intelligence had led him to the conclusion that there was a genetic component to the average racial differences in IQ. This was, of course, volatile stuff, and coming as it did in the midst of the civil rights movement, it was inflammatory.

I had read one of Jensen’s key papers and was persuaded that he was a serious scholar and not a bigot. As a social psychologist, however, I thought Jensen was overlooking environmental and situational explanations for racial differences. I was reluctant to invite him to give a colloquium not because he was controversial but because, given our limited departmental budget, I would have preferred to invite psychologists who I thought were doing far more interesting research. But the graduate student committee argued that it would be exciting for them to have the opportunity to challenge Jensen’s conclusions in a face-to-face, friendly confrontation. As chair, I was not looking to foment controversy, nor was I looking to avoid it. I agreed to invite him.

On the phone Jensen accepted my invitation and then astonished me by demanding protection; he explained that, during the preceding few months at several universities, students had shouted him down, spat on him, and jostled him. I assured him that would not happen at Santa Cruz because we had an open-minded student body and, even more important, our colloquia had always consisted of small gatherings of about ten graduate students and seven or eight faculty members, sitting around a table in a seminar room. I joked that our graduate students hardly ever spat on our guests. Jensen was not amused.

Then, much to my surprise and disappointment, the night before his arrival, a few hundred students staged a rally at which they burned one of his books and some of his research publications and announced that they intended to storm the colloquium the next evening. In Texas I had become all too familiar with the intolerance of right-wingers, so it was a shock to encounter the intolerance of liberals—people whose values I shared but whose tactics could be just as undemocratic as those I had encountered in Austin.

The anger and potential violence of the students posed a dilemma for me. I had guaranteed Jensen safety; the prospect of two hundred students “storming” a seminar room that held twenty was alarming. Should I have the cops come out to protect him? Should I call off the meeting? Neither choice was acceptable. I did not want to create the conditions for a student-police confrontation, but neither did I want to capitulate to undemocratic rowdiness. After a good deal of thought, I arrived at what I considered to be a judicious solution: I decided to hold the seminar at a professor’s home and posted a notice on the seminar door announcing that the meeting had been moved off campus. When a horde of undergraduates arrived at the seminar room and found no one there, they were furious.

The next day I was vilified in the student newspaper, which called me a racist for inviting Jensen and a coward for not letting the students get at him. The irony was not lost on me. Ten years earlier, in Austin, I had been called a “nigger lover.” Now, in Santa Cruz, I found myself accused of being a racist. Indeed, in a bizarre echo of Austin, that night I received an unpleasant phone call at home. It was from an angry student rather than a gravelly voiced man, and it came at eight at night rather than two in the morning, but it was disquieting nonetheless.

“Are you going to be keeping your office hours in the patio outside the Kresge coffeehouse tomorrow, as usual?”

“Of course,” I responded.

He said, ominously, “You better be there.”

When I arrived at the patio and approached my usual table, there were three students waiting for me: Hal, Neal, and Julie Aronson. (Josh was still in high school.) Vera had told them about the phone call and the possibility of trouble, and they showed up to offer their dad moral support and, if needed, physical protection. Ten minutes later a few dozen students, some carrying torches and all chanting “Aronson’s a racist,” marched up the hill to the patio and surrounded my table. They activated a tape recorder and recited into the microphone a list of their grievances against me. Then they thrust the microphone in my face and said, “What do you have to say to that?”

I did what almost any liberal professor would have done: I gave them a five-minute lecture extolling the beauty of the First Amendment. I told them that I regretted shutting students out of Jensen’s talk, but the book burning and rowdiness of the previous evening had left me no choice. I told them that the point of education is not simply to confirm what we believe but to hear and discuss the ideas of serious scholars who hold a wide range of opinions—some of which we will disagree with, some of which we may even find offensive. At a university, learning often emerges from argument, but the argument must be civil. The students listened. A few even applauded. They dispersed quietly.

I looked over at my kids. They were grinning.

“Not bad, Dad,” said Hal.

“Very good,” said Julie.

“Let’s get some coffee,” said Neal.

It took me a while to overcome the distress I had felt, but I came to see the Jensen incident as reflecting a combination of student qualities that I cherish: being feisty and teachable. I’d never encountered that combination before, not even at Harvard. In the main, Harvard undergrads were more sophisticated and knowledgeable than UCSC students, but in my experience they also seemed more conventional. I admired and enjoyed the UCSC students’ willingness to speak their minds, ruffle feathers, and listen, and they repaid me by flocking to my introductory social psychology course. In 1979, when the Alumnae Association decided to establish an annual Distinguished Teaching Award, they honored me as their first recipient.

In the late 1970s and early 1980s another transformative change in American society was gathering steam. Whereas T-groups were all about lowering self-imposed barriers between people (“touching others is good, healthy, humane”), society, spurred by the women’s movement, was moving toward respecting boundaries (“touching others is disrespectful, inappropriate, and patronizing”). I had learned to value the importance of expressing positive feelings toward other people, verbally and physically. Of course, I understood and accepted the feminist critique of inappropriate touching for the purpose of demonstrating power or dominance. Needless to say, uninvited touching is wrong, and it is as wrong in an encounter group as it is in the larger world. But before long few people were making the distinction between appropriate and inappropriate touches; all touches were being viewed with suspicion. I felt caught between these two conflicting social philosophies.

One semester I had four graduate teaching assistants for my large introductory social psychology course: Erica and Suzanne, third-year students who had been working with me since their arrival and had become personal friends of Vera’s and mine; Alex, a second-year student who was just beginning to work with me; and a young woman I’ll call Lois, a first-year student I hardly knew. At the end of the term, as we were reviewing what had happened in the course, Lois turned to me and said, in an accusatory tone, “I have a bone to pick with you. I couldn’t help noticing that when you interact with your teaching assistants, you touch the women far more frequently than you touch Alex. I find that to be sexist and demeaning.”

Puzzled, I replied, “Yes, I agree with your observation. Suzanne, Erica, and I, when we converse, do frequently reach out and touch each other on the arm or shoulder; but have I ever touched you?”

“No,” she said.

“And I don’t touch Alex, right?”

“Right,” she said.

“Erica, Suzanne, and I have known one another for years. Isn’t it a more parsimonious explanation,” I suggested, “that I touch friends more frequently than people I don’t know well?”

“Maybe,” she said. But she made it clear that she was not convinced.

Suzanne and Erica recounted the incident to Vera with much amusement, but I wasn’t sure whether to laugh or cry. Where have you gone, Aron Gurwitsch? In 1953, when my fine old philosophy professor placed his hand on top of my head and said, “Good boy,” I saw it for what it was: an expression of warmth and affection, a gesture of intellectual camaraderie. In today’s climate of suspicion, would students see that as demeaning or even as a sexual pass? That exchange with Lois epitomized the atmosphere that was developing at UCSC and most other colleges across the country.

In the late 1970s and early 1980s another transformative change in American society was gathering steam. Whereas T-groups were all about lowering self-imposed barriers between people (“touching others is good, healthy, humane”), society, spurred by the women’s movement, was moving toward respecting boundaries (“touching others is disrespectful, inappropriate, and patronizing”). I had learned to value the importance of expressing positive feelings toward other people, verbally and physically. Of course, I understood and accepted the feminist critique of inappropriate touching for the purpose of demonstrating power or dominance. Needless to say, uninvited touching is wrong, and it is as wrong in an encounter group as it is in the larger world. But before long few people were making the distinction between appropriate and inappropriate touches; all touches were being viewed with suspicion. I felt caught between these two conflicting social philosophies.

One semester I had four graduate teaching assistants for my large introductory social psychology course: Erica and Suzanne, third-year students who had been working with me since their arrival and had become personal friends of Vera’s and mine; Alex, a second-year student who was just beginning to work with me; and a young woman I’ll call Lois, a first-year student I hardly knew. At the end of the term, as we were reviewing what had happened in the course, Lois turned to me and said, in an accusatory tone, “I have a bone to pick with you. I couldn’t help noticing that when you interact with your teaching assistants, you touch the women far more frequently than you touch Alex. I find that to be sexist and demeaning.”

Puzzled, I replied, “Yes, I agree with your observation. Suzanne, Erica, and I, when we converse, do frequently reach out and touch each other on the arm or shoulder; but have I ever touched you?”

“No,” she said.

“And I don’t touch Alex, right?”

“Right,” she said.

“Erica, Suzanne, and I have known one another for years. Isn’t it a more parsimonious explanation,” I suggested, “that I touch friends more frequently than people I don’t know well?”

“Maybe,” she said. But she made it clear that she was not convinced.

Suzanne and Erica recounted the incident to Vera with much amusement, but I wasn’t sure whether to laugh or cry. Where have you gone, Aron Gurwitsch? In 1953, when my fine old philosophy professor placed his hand on top of my head and said, “Good boy,” I saw it for what it was: an expression of warmth and affection, a gesture of intellectual camaraderie. In today’s climate of suspicion, would students see that as demeaning or even as a sexual pass? That exchange with Lois epitomized the atmosphere that was developing at UCSC and most other colleges across the country.

One morning a representative of the recently formed sexual harassment office came to the psychology faculty meeting to lay out the guidelines for faculty-student deportment. I found almost all of these guidelines sensible and reasonable and agreed with most of what she said. She spoke not only of the obvious ethical wrongdoing of abusing professorial power for sexual advantage but also of more subtle violations. Students, she said, often have crushes on their professors, but that doesn’t mean they want a sexual affair; indeed, they often don’t know what they want. But then she said something that didn’t sound so reasonable. Under the new policy, male faculty members were urged to refrain from inviting female graduate students to research conferences. Steve Wright, a young social psychologist, immediately spoke up. Some conferences, he said, like the meeting of the Society of Experimental Social Psychology, attract the best researchers and the leaders of our field. Attending these meetings presented a great opportunity for our graduate students to become acquainted with the very people who might one day offer them teaching positions. He added, correctly, that this new policy would put our female graduate students at a disadvantage in the job market.

The sexual harassment official shrugged. She had no answer to Steve’s concerns and went on to her next rule: All professors were thenceforth obliged to inform her office of anything they might hear about a possible sexual relationship between a teacher and a student. This sounded so strange that I thought I might have misunderstood her. I raised my hand.

“Let me get this straight,” I said. “If a student tells me that she thinks that professor X might be sleeping with student Y, I am supposed to report this rumor to your office?”

“That’s right,” she said.

I was incredulous. I looked around the room at my colleagues, but no one flinched. I had no way of knowing whether they thought that reporting rumors was a good idea, were too frightened to object, or were simply complacent. Or perhaps, like me, they thought the rule was bizarre and had no intention of complying but saw no reason to speak up.

My mind wandered. I remembered walking across campus one sunny spring day when a beautiful young woman suddenly leaped out from behind a tree and flung herself into my arms. We hugged. The woman was my daughter, Julie, a sophomore at the time. A few weeks later one of Julie’s housemates casually mentioned that her boyfriend, Ron, had asked if Julie was still having an affair with Professor Aronson—a friend of his had actually seen them necking on campus. She laughed and informed Ron that Julie’s last name was Aronson. That’s how rumors work, of course, transforming a hug into necking, and necking into an affair. But what if Julie’s last name had not been Aronson and the student who had hugged me was doing so out of playful affection? Would all bystanders be required to report it to the sexual harassment office? What was becoming of our community? After a long pause, I spoke up. “I’m not going to report rumors,” I said.

The meeting was acquiring a Kafkaesque quality. I thought about my baseball buddies, Billy and Al, and how, back in 1951, they had mocked me for coming out against Joseph McCarthy and his political fishing expeditions. “Do they teach you that stuff up there at the college?” they had asked. Now, some four decades later, hearing echoes of that time, I felt my head was spinning. As a liberal I agreed with the goals of the sexual harassment official. But as a social psychologist I knew that the recommended methods were likely to backfire and possibly become dangerous. Asking people to report idle rumors is a totalitarian tactic that spreads fear, suppresses dissent, and can sweep the innocent into the net of the guilty.

I took another look around the room at my colleagues. Three of them were married to women who had been their students. Would the new rules make these marriages retroactively “inappropriate”? The university’s rules were designed to protect young women who, as the official had told us, “don’t know what they want,” but what about mature, capable women who do know what they want? Did the university really want to put itself into the business of making that discrimination—this love affair is good, but this other one is bad?

A few days later my friend Dane Archer, a sociologist, strode into my office fresh from his own departmental meeting with a sexual harassment official. Like me, Dane was appalled by the demand to report rumors, but he was amused by the clash between the new rules and the fact that some of our colleagues were married to their former students. He had just read a tongue-in-cheek essay in the Harvard alumni magazine in which John Kenneth Galbraith, the distinguished economist, had offered to turn in his marriage license because his beloved wife of some sixty years had been his student when they married. “But I think Galbraith got it wrong,” Dane said. “The way I interpret the current regulations, we professors are allowed to marry our students. We just aren’t allowed to date them.”

Several weeks later a few unsigned fliers were posted on trees and bulletin boards across the campus. They were cleverly worded—simply a request for information about a couple of popular male professors. Neither man was actually accused of sexual harassment. I shook my head in dismay. I didn’t take it seriously; I thought it was a childish prank. Then, one morning, several of these handwritten fliers appeared with my name on them, and suddenly the prank wasn’t funny. They read:

One morning a representative of the recently formed sexual harassment office came to the psychology faculty meeting to lay out the guidelines for faculty-student deportment. I found almost all of these guidelines sensible and reasonable and agreed with most of what she said. She spoke not only of the obvious ethical wrongdoing of abusing professorial power for sexual advantage but also of more subtle violations. Students, she said, often have crushes on their professors, but that doesn’t mean they want a sexual affair; indeed, they often don’t know what they want. But then she said something that didn’t sound so reasonable. Under the new policy, male faculty members were urged to refrain from inviting female graduate students to research conferences. Steve Wright, a young social psychologist, immediately spoke up. Some conferences, he said, like the meeting of the Society of Experimental Social Psychology, attract the best researchers and the leaders of our field. Attending these meetings presented a great opportunity for our graduate students to become acquainted with the very people who might one day offer them teaching positions. He added, correctly, that this new policy would put our female graduate students at a disadvantage in the job market.

The sexual harassment official shrugged. She had no answer to Steve’s concerns and went on to her next rule: All professors were thenceforth obliged to inform her office of anything they might hear about a possible sexual relationship between a teacher and a student. This sounded so strange that I thought I might have misunderstood her. I raised my hand.

“Let me get this straight,” I said. “If a student tells me that she thinks that professor X might be sleeping with student Y, I am supposed to report this rumor to your office?”

“That’s right,” she said.

I was incredulous. I looked around the room at my colleagues, but no one flinched. I had no way of knowing whether they thought that reporting rumors was a good idea, were too frightened to object, or were simply complacent. Or perhaps, like me, they thought the rule was bizarre and had no intention of complying but saw no reason to speak up.

My mind wandered. I remembered walking across campus one sunny spring day when a beautiful young woman suddenly leaped out from behind a tree and flung herself into my arms. We hugged. The woman was my daughter, Julie, a sophomore at the time. A few weeks later one of Julie’s housemates casually mentioned that her boyfriend, Ron, had asked if Julie was still having an affair with Professor Aronson—a friend of his had actually seen them necking on campus. She laughed and informed Ron that Julie’s last name was Aronson. That’s how rumors work, of course, transforming a hug into necking, and necking into an affair. But what if Julie’s last name had not been Aronson and the student who had hugged me was doing so out of playful affection? Would all bystanders be required to report it to the sexual harassment office? What was becoming of our community? After a long pause, I spoke up. “I’m not going to report rumors,” I said.

The meeting was acquiring a Kafkaesque quality. I thought about my baseball buddies, Billy and Al, and how, back in 1951, they had mocked me for coming out against Joseph McCarthy and his political fishing expeditions. “Do they teach you that stuff up there at the college?” they had asked. Now, some four decades later, hearing echoes of that time, I felt my head was spinning. As a liberal I agreed with the goals of the sexual harassment official. But as a social psychologist I knew that the recommended methods were likely to backfire and possibly become dangerous. Asking people to report idle rumors is a totalitarian tactic that spreads fear, suppresses dissent, and can sweep the innocent into the net of the guilty.

I took another look around the room at my colleagues. Three of them were married to women who had been their students. Would the new rules make these marriages retroactively “inappropriate”? The university’s rules were designed to protect young women who, as the official had told us, “don’t know what they want,” but what about mature, capable women who do know what they want? Did the university really want to put itself into the business of making that discrimination—this love affair is good, but this other one is bad?

A few days later my friend Dane Archer, a sociologist, strode into my office fresh from his own departmental meeting with a sexual harassment official. Like me, Dane was appalled by the demand to report rumors, but he was amused by the clash between the new rules and the fact that some of our colleagues were married to their former students. He had just read a tongue-in-cheek essay in the Harvard alumni magazine in which John Kenneth Galbraith, the distinguished economist, had offered to turn in his marriage license because his beloved wife of some sixty years had been his student when they married. “But I think Galbraith got it wrong,” Dane said. “The way I interpret the current regulations, we professors are allowed to marry our students. We just aren’t allowed to date them.”

Several weeks later a few unsigned fliers were posted on trees and bulletin boards across the campus. They were cleverly worded—simply a request for information about a couple of popular male professors. Neither man was actually accused of sexual harassment. I shook my head in dismay. I didn’t take it seriously; I thought it was a childish prank. Then, one morning, several of these handwritten fliers appeared with my name on them, and suddenly the prank wasn’t funny. They read: Meanwhile, my research was flourishing. Tom Pettigrew, Dane Archer, Marti Hope Gonzales, and I spent several years doing research on energy conservation, which had come to public attention with a jolt in the 1970s; Diane Bridgeman and I were extending our experiments on the jigsaw classroom. Then, in the 1980s, our campus, like so many others, was abuzz about the emergence and rise of a horrible new disease called AIDS. Because there was no cure in sight, the challenge was to prevent it. And because almost all AIDS infections were occurring through voluntary sexual behavior, it immediately made prevention a social-psychological problem rather than a medical one: how to persuade sexually active people to use condoms.

Scary ads proved to be utterly ineffective. Our Health Center conducted a vigorous campaign, handing out pamphlets and presenting illustrated lectures and demonstrations, but still only about 17 percent of sexually active students were using condoms regularly. The Health Center asked me to assist them in beefing up their campaign.

First, my graduate students and I conducted a survey to determine why most undergrads weren’t using condoms. No surprise: They considered condoms inconvenient and unromantic, antiseptic rather than exciting. To counteract that common belief, we produced and directed a brief video depicting an attractive young couple using condoms in a romantic and sexy way. In the video the woman puts the condom on the man as an integral part of foreplay. I hasten to add that our video would have been R-rated rather than X-rated. There was almost no nudity involved, and putting on the condom, though accompanied by erotic moaning and groaning, took place under the blanket. Nonetheless, our talented volunteer actors portrayed sexual pleasure convincingly. This procedure might have been considered risky, or even foolhardy, given the existing political climate at UCSC. But I felt that the problem we were addressing was too important to shy away from, and the university’s Internal Review Board agreed. They unanimously approved of the experimental procedure.

The video proved to be effective, but only for a short time. Condom use increased for a few weeks and then declined sharply. Follow-up interviews revealed that the video had opened the students’ minds to the erotic possibilities of condom use, but once they tried it a few times, they realized that they were not having nearly as much fun as the couple in the video, so they stopped using them.

Undaunted, I tried a different tack. I knew from my years of research on cognitive-dissonance theory that change is greater and lasts longer when behavior precedes attitude, when people are not simply admonished to change but placed in a situation that induces them to convince themselves to change. For example, in our initiation experiment, we didn’t try to convince students that the boring group they had joined was interesting. That strategy would have failed, just as the condom ad campaigns and the R-rated video had failed. Rather, we put people through a severe initiation that induced them to persuade themselves that the group was interesting.

So how could we induce people to persuade themselves to use condoms? My first thought was to try to apply the Festinger/Carlsmith paradigm, where they induced people to tell a lie (“Packing spools into a box is really interesting!”) for only a small amount of money, thereby creating dissonance; the participants could reduce dissonance by convincing themselves that the task really was interesting. But the paradigm would not work in this situation because, in effect, there was nothing to lie about. Sexually active students were fully aware that AIDS was a serious problem and that condoms were a smart way to avoid contracting the virus. They knew all that and still weren’t using them.

In an attempt to figure it out, I created a thought experiment. Suppose you are a sexually active college student who doesn’t use condoms. On going home for Christmas, your seventeen-year-old brother, who has just discovered sex, boasts to you about his sexual encounters. Being a responsible older sibling, you warn him about the dangers of AIDS and other sexually transmitted diseases and urge him to use condoms. Suppose I overheard this exchange and said to you, “That was good advice you gave your kid brother. By the way, how often do you use condoms?” This challenge forces you to become mindful of the dissonance between your self-concept as a person of integrity and the fact that you are behaving hypocritically. How might you reduce dissonance? You could agree that you are a hypocrite, or you could start to practice what you have just finished preaching. You could use condoms yourself.

And that is how, in 1989, I came to invent the hypocrisy paradigm. In a series of experiments with my graduate students Jeff Stone and Carrie Fried, we invited sexually active students to deliver a speech about the dangers of AIDS and the importance of using condoms. We videotaped each speech and informed the speakers that their video would be shown to high school students as part of a sex-education class. In the crucial condition, after they made the videotape, we got them to talk about the situations where they had not used condoms themselves, making them mindful of their own hypocrisy. And it worked.

Naturally, we could not follow them into their bedrooms, but we did get a secondary behavioral measure: their actual purchase of condoms. Students in the “hypocrisy” condition bought more condoms than students in the control condition who made the same videotaped speech but were not made mindful of the fact that their own behavior contradicted their stated beliefs. And we had reason to believe that they were not only buying condoms but also using them. Several months later we conducted a follow-up survey, disguised as an assessment of sexual behavior on campus, by hiring undergraduates to telephone all the students who had participated in the study. We found that those who had been in the hypocrisy condition were continuing to use condoms at three times the rate of those in the control condition.

My next hypocrisy experiment, with my graduate student Ruth Thibodeau, was designed to get students to conserve water. California was going through one of its periodic droughts, and the campus administration was urging students to use less water, again with little effect. We invited students to sign a poster urging everyone to conserve water by taking shorter showers. (Students were happy to sign the poster; after all, everybody believes in conserving water.) We then made half of them mindful of their hypocrisy by asking them to estimate how long their own most recent showers had been. Afterward, our confederates, who were loitering in the field-house shower room, surreptitiously timed the participants’ showers. Students in the hypocrisy condition showered, on average, for three and a half minutes—a fraction of the time spent in the shower by those in the control condition.

Meanwhile, my research was flourishing. Tom Pettigrew, Dane Archer, Marti Hope Gonzales, and I spent several years doing research on energy conservation, which had come to public attention with a jolt in the 1970s; Diane Bridgeman and I were extending our experiments on the jigsaw classroom. Then, in the 1980s, our campus, like so many others, was abuzz about the emergence and rise of a horrible new disease called AIDS. Because there was no cure in sight, the challenge was to prevent it. And because almost all AIDS infections were occurring through voluntary sexual behavior, it immediately made prevention a social-psychological problem rather than a medical one: how to persuade sexually active people to use condoms.

Scary ads proved to be utterly ineffective. Our Health Center conducted a vigorous campaign, handing out pamphlets and presenting illustrated lectures and demonstrations, but still only about 17 percent of sexually active students were using condoms regularly. The Health Center asked me to assist them in beefing up their campaign.

First, my graduate students and I conducted a survey to determine why most undergrads weren’t using condoms. No surprise: They considered condoms inconvenient and unromantic, antiseptic rather than exciting. To counteract that common belief, we produced and directed a brief video depicting an attractive young couple using condoms in a romantic and sexy way. In the video the woman puts the condom on the man as an integral part of foreplay. I hasten to add that our video would have been R-rated rather than X-rated. There was almost no nudity involved, and putting on the condom, though accompanied by erotic moaning and groaning, took place under the blanket. Nonetheless, our talented volunteer actors portrayed sexual pleasure convincingly. This procedure might have been considered risky, or even foolhardy, given the existing political climate at UCSC. But I felt that the problem we were addressing was too important to shy away from, and the university’s Internal Review Board agreed. They unanimously approved of the experimental procedure.

The video proved to be effective, but only for a short time. Condom use increased for a few weeks and then declined sharply. Follow-up interviews revealed that the video had opened the students’ minds to the erotic possibilities of condom use, but once they tried it a few times, they realized that they were not having nearly as much fun as the couple in the video, so they stopped using them.

Undaunted, I tried a different tack. I knew from my years of research on cognitive-dissonance theory that change is greater and lasts longer when behavior precedes attitude, when people are not simply admonished to change but placed in a situation that induces them to convince themselves to change. For example, in our initiation experiment, we didn’t try to convince students that the boring group they had joined was interesting. That strategy would have failed, just as the condom ad campaigns and the R-rated video had failed. Rather, we put people through a severe initiation that induced them to persuade themselves that the group was interesting.

So how could we induce people to persuade themselves to use condoms? My first thought was to try to apply the Festinger/Carlsmith paradigm, where they induced people to tell a lie (“Packing spools into a box is really interesting!”) for only a small amount of money, thereby creating dissonance; the participants could reduce dissonance by convincing themselves that the task really was interesting. But the paradigm would not work in this situation because, in effect, there was nothing to lie about. Sexually active students were fully aware that AIDS was a serious problem and that condoms were a smart way to avoid contracting the virus. They knew all that and still weren’t using them.

In an attempt to figure it out, I created a thought experiment. Suppose you are a sexually active college student who doesn’t use condoms. On going home for Christmas, your seventeen-year-old brother, who has just discovered sex, boasts to you about his sexual encounters. Being a responsible older sibling, you warn him about the dangers of AIDS and other sexually transmitted diseases and urge him to use condoms. Suppose I overheard this exchange and said to you, “That was good advice you gave your kid brother. By the way, how often do you use condoms?” This challenge forces you to become mindful of the dissonance between your self-concept as a person of integrity and the fact that you are behaving hypocritically. How might you reduce dissonance? You could agree that you are a hypocrite, or you could start to practice what you have just finished preaching. You could use condoms yourself.

And that is how, in 1989, I came to invent the hypocrisy paradigm. In a series of experiments with my graduate students Jeff Stone and Carrie Fried, we invited sexually active students to deliver a speech about the dangers of AIDS and the importance of using condoms. We videotaped each speech and informed the speakers that their video would be shown to high school students as part of a sex-education class. In the crucial condition, after they made the videotape, we got them to talk about the situations where they had not used condoms themselves, making them mindful of their own hypocrisy. And it worked.

Naturally, we could not follow them into their bedrooms, but we did get a secondary behavioral measure: their actual purchase of condoms. Students in the “hypocrisy” condition bought more condoms than students in the control condition who made the same videotaped speech but were not made mindful of the fact that their own behavior contradicted their stated beliefs. And we had reason to believe that they were not only buying condoms but also using them. Several months later we conducted a follow-up survey, disguised as an assessment of sexual behavior on campus, by hiring undergraduates to telephone all the students who had participated in the study. We found that those who had been in the hypocrisy condition were continuing to use condoms at three times the rate of those in the control condition.

My next hypocrisy experiment, with my graduate student Ruth Thibodeau, was designed to get students to conserve water. California was going through one of its periodic droughts, and the campus administration was urging students to use less water, again with little effect. We invited students to sign a poster urging everyone to conserve water by taking shorter showers. (Students were happy to sign the poster; after all, everybody believes in conserving water.) We then made half of them mindful of their hypocrisy by asking them to estimate how long their own most recent showers had been. Afterward, our confederates, who were loitering in the field-house shower room, surreptitiously timed the participants’ showers. Students in the hypocrisy condition showered, on average, for three and a half minutes—a fraction of the time spent in the shower by those in the control condition.

The hypocrisy paradigm extended the reach of dissonance theory and proved to be a fruitful way of exploring human behavior, generating a plethora of interesting hypotheses. Yet I was inclined to let others test them. As for me, I felt it was precisely the right moment to say farewell to the social psychological laboratory. I had just turned sixty and realized that I had gradually been losing my zeal for the nuts and bolts of doing experiments. With the hypocrisy studies completed, I would be leaving on a high, just as an aging baseball player dreams of ending his career by hitting a home run his last time at bat. Once Jeff, Carrie, and Ruth had earned their doctorates and moved on to teaching positions at fine universities, I lost interest in mentoring new students and found myself more or less marking time as my laboratory rooms gathered dust.

As I might have predicted from the Life Cycle course that Ellen Suckiel and I had been teaching, my priorities had shifted. I had grown impatient with doing experiments because I no longer wanted to contribute one brick at a time to the edifice of our knowledge in social psychology. What I did want to do in my old age was put those bricks together, building on what I already knew. I had a strong desire to synthesize my knowledge and experience, by continuing to teach large lecture courses in the hope of inspiring undergraduates and by writing books for general audiences. My departmental colleague Anthony Pratkanis and I had long shared an interest in the uses and abuses of persuasion, so we collaborated on Age of Propaganda, a general-audience book in which we combined social-psychological findings with our insights and interpretations.

By this time some of my close friends had retired, but the thought of retirement had never crossed my mind. For several years after my brother died, I was certain that I too would die young. Who needs to think about retirement when he will die in his thirties? As the years rolled by, morphing into decades, I was forced to abandon that tragic-romantic self-image. Even so, I could not imagine leaving the university. I loved teaching so much that I was sure I would remain on that lecture platform until they had to carry me out feet first. I secretly harbored the fantasy that I would collapse and die of a heart attack at ninety-five, while delivering an impassioned lecture on dissonance theory, in a packed auditorium, standing room only, as admiring students leaned forward, hanging on my every word.

My fantasy notwithstanding, by 1994 my changing priorities had created something of an ethical dilemma. I could take the easy way out by continuing to teach, writing books, and collecting the relatively hefty salary that the university was paying me. But one of the primary reasons that I had been hired was my ability to do research and train graduate students to be good scientists so that they could take positions in academia, where they could continue to produce research and train their graduate students to do the same. Should I give up training graduate students? This would mean shortchanging the university. Should I go through the motions of training them even though I had lost my enthusiasm for doing experiments? This would be shortchanging the students who would be coming to UCSC to work with me.

While I was wrestling with these questions, California fell into one of its recurring major financial crises (as common as its droughts). The legislature required all state universities to cut their expenditures drastically, and the universities responded by encouraging senior professors to take early retirement. Because the retirement fund, unlike the state budget, was flush, we could retire at approximately 75 percent of our annual salary. As an inducement to those who enjoyed teaching, they guaranteed that we could continue to teach our favorite course for at least five years, and perhaps indefinitely, for a small honorarium.

The offer resolved my ethical dilemma; I could teach without doing research. Still, the word “retirement” sounded noxious to my ears; it seemed final—like death. I therefore did what most participants in social psychological experiments do: I checked to see what other people were doing. Both of my most senior colleagues in psychology, Bill Domhoff and Tom Pettigrew, were strongly leaning toward taking early retirement. And so, like the elderly people I used to watch wading into the cold surf at Revere Beach when I was a boy, the three of us held hands and took the plunge together.

Bill, Tom, and I retired. But we were still teaching our favorite courses; Bill and Tom taught their seminars, and I had my introductory social psychology course with three hundred undergraduates. This arrangement lasted until a new chair of the department took over and unilaterally decided not to renew the teaching agreement, claiming that there was not enough money in the budget for the three of us. This explanation made no sense to me; intro social psychology was a basic course for majors and, because of my small stipend, was costing the university less than thirty dollars per student. The students were up in arms and protested vigorously, without success. I was out of a job.

Fortunately, as soon as the Stanford Psychology Department heard this news, they invited me to teach one course per year, as a distinguished visiting professor, for as long as I wanted to. On what must have been a slow news day in May 2000, the headline on the front page of the Santa Cruz Sentinel read “Famed Social Psychologist Elliot Aronson Leaves UCSC for Stanford.” The article began, “Stanford University is snapping up esteemed psychology professor and author Elliot Aronson now that UC Santa Cruz is cutting him loose. The UCSC psychology department cited financial reasons for ending its relationship with the semi-retired Aronson, arguably the most famous living American social psychologist.” The story was gratifying, but it barely soothed my sorrow at leaving the university I had served for twenty-five years and the feisty, teachable students I was so very fond of.

The Stanford Psychology Department went out of its way to make me feel at home, inviting me to teach anything I wanted. I chose a course on social influence, the first subject I’d ever taught as a new and nervous assistant professor at Harvard. The course attracted a great many students, graduates and undergraduates, across several disciplines. There was something sweet and satisfying about ending my teaching career at the very place where, forty years earlier, I had first become a social psychologist. However, my thoughts were not about the end of an era in my life; they were of a new beginning. My fantasy of teaching until age ninety-five might come true after all! But as Woody Allen is said to have said, “If you want to make God laugh, tell him about your plans.”

在线 阅读网:hTTp://wwW.yuedu88.com/

The hypocrisy paradigm extended the reach of dissonance theory and proved to be a fruitful way of exploring human behavior, generating a plethora of interesting hypotheses. Yet I was inclined to let others test them. As for me, I felt it was precisely the right moment to say farewell to the social psychological laboratory. I had just turned sixty and realized that I had gradually been losing my zeal for the nuts and bolts of doing experiments. With the hypocrisy studies completed, I would be leaving on a high, just as an aging baseball player dreams of ending his career by hitting a home run his last time at bat. Once Jeff, Carrie, and Ruth had earned their doctorates and moved on to teaching positions at fine universities, I lost interest in mentoring new students and found myself more or less marking time as my laboratory rooms gathered dust.

As I might have predicted from the Life Cycle course that Ellen Suckiel and I had been teaching, my priorities had shifted. I had grown impatient with doing experiments because I no longer wanted to contribute one brick at a time to the edifice of our knowledge in social psychology. What I did want to do in my old age was put those bricks together, building on what I already knew. I had a strong desire to synthesize my knowledge and experience, by continuing to teach large lecture courses in the hope of inspiring undergraduates and by writing books for general audiences. My departmental colleague Anthony Pratkanis and I had long shared an interest in the uses and abuses of persuasion, so we collaborated on Age of Propaganda, a general-audience book in which we combined social-psychological findings with our insights and interpretations.

By this time some of my close friends had retired, but the thought of retirement had never crossed my mind. For several years after my brother died, I was certain that I too would die young. Who needs to think about retirement when he will die in his thirties? As the years rolled by, morphing into decades, I was forced to abandon that tragic-romantic self-image. Even so, I could not imagine leaving the university. I loved teaching so much that I was sure I would remain on that lecture platform until they had to carry me out feet first. I secretly harbored the fantasy that I would collapse and die of a heart attack at ninety-five, while delivering an impassioned lecture on dissonance theory, in a packed auditorium, standing room only, as admiring students leaned forward, hanging on my every word.

My fantasy notwithstanding, by 1994 my changing priorities had created something of an ethical dilemma. I could take the easy way out by continuing to teach, writing books, and collecting the relatively hefty salary that the university was paying me. But one of the primary reasons that I had been hired was my ability to do research and train graduate students to be good scientists so that they could take positions in academia, where they could continue to produce research and train their graduate students to do the same. Should I give up training graduate students? This would mean shortchanging the university. Should I go through the motions of training them even though I had lost my enthusiasm for doing experiments? This would be shortchanging the students who would be coming to UCSC to work with me.

While I was wrestling with these questions, California fell into one of its recurring major financial crises (as common as its droughts). The legislature required all state universities to cut their expenditures drastically, and the universities responded by encouraging senior professors to take early retirement. Because the retirement fund, unlike the state budget, was flush, we could retire at approximately 75 percent of our annual salary. As an inducement to those who enjoyed teaching, they guaranteed that we could continue to teach our favorite course for at least five years, and perhaps indefinitely, for a small honorarium.

The offer resolved my ethical dilemma; I could teach without doing research. Still, the word “retirement” sounded noxious to my ears; it seemed final—like death. I therefore did what most participants in social psychological experiments do: I checked to see what other people were doing. Both of my most senior colleagues in psychology, Bill Domhoff and Tom Pettigrew, were strongly leaning toward taking early retirement. And so, like the elderly people I used to watch wading into the cold surf at Revere Beach when I was a boy, the three of us held hands and took the plunge together.

Bill, Tom, and I retired. But we were still teaching our favorite courses; Bill and Tom taught their seminars, and I had my introductory social psychology course with three hundred undergraduates. This arrangement lasted until a new chair of the department took over and unilaterally decided not to renew the teaching agreement, claiming that there was not enough money in the budget for the three of us. This explanation made no sense to me; intro social psychology was a basic course for majors and, because of my small stipend, was costing the university less than thirty dollars per student. The students were up in arms and protested vigorously, without success. I was out of a job.

Fortunately, as soon as the Stanford Psychology Department heard this news, they invited me to teach one course per year, as a distinguished visiting professor, for as long as I wanted to. On what must have been a slow news day in May 2000, the headline on the front page of the Santa Cruz Sentinel read “Famed Social Psychologist Elliot Aronson Leaves UCSC for Stanford.” The article began, “Stanford University is snapping up esteemed psychology professor and author Elliot Aronson now that UC Santa Cruz is cutting him loose. The UCSC psychology department cited financial reasons for ending its relationship with the semi-retired Aronson, arguably the most famous living American social psychologist.” The story was gratifying, but it barely soothed my sorrow at leaving the university I had served for twenty-five years and the feisty, teachable students I was so very fond of.

The Stanford Psychology Department went out of its way to make me feel at home, inviting me to teach anything I wanted. I chose a course on social influence, the first subject I’d ever taught as a new and nervous assistant professor at Harvard. The course attracted a great many students, graduates and undergraduates, across several disciplines. There was something sweet and satisfying about ending my teaching career at the very place where, forty years earlier, I had first become a social psychologist. However, my thoughts were not about the end of an era in my life; they were of a new beginning. My fantasy of teaching until age ninety-five might come true after all! But as Woody Allen is said to have said, “If you want to make God laugh, tell him about your plans.”

在线 阅读网:hTTp://wwW.yuedu88.com/

Lecturing, 1994 (top).

Budding social psychologist Josh and his first mentor at their favorite coffeehouse, 1989.

When we moved to Santa Cruz from Texas, I felt I was in paradise. The weather was heavenly. I was near an ocean again. And I was at a liberal institution with a liberal student body. As a place to live, Santa Cruz was everything Vera and I had hoped it would be for ourselves and our family, then and now; three of our four children still live in or near Santa Cruz. At the university the highs were higher than at any place I had ever taught; however, the lows were also lower.

During my first three years on campus, my office was next to a philosopher on one side and a physicist on the other; across the corridor was a historian, and two doors down, a poet. One result of this happy proximity was that the philosopher next door to me, Ellen Suckiel, and I developed a course we called Philosophical and Psychological Foundations of the Life Cycle that, year after year, received the highest student evaluations on campus. In practice the college system at UCSC was a wonderful way to teach undergraduates because it combined the best aspects of a small private college, like Swarthmore or Reed, with the facilities of a large state university. Hal blossomed there; his excitement (and mine) inspired Neal, Julie, and Josh to follow him to UCSC.

Initially, the living-learning community at Kresge College worked beautifully. As in all of the colleges, students could take standard university courses in traditional subjects, such as history, psychology, or biology, as well as special interdisciplinary seminars. At Kresge the seminars added a level of intensity to the usual academic discussion, because they were often run as T-groups. The students were required to learn the course material, and professors retained their authority to make intellectual demands, set requirements, and evaluate the students’ performance. But students also learned about themselves, their relationship to their peers, and ways to communicate clearly and effectively. The T-groups I had been conducting in Bethel, Maine, had a finite duration, about two weeks, and when they were over, participants dispersed to their home cities—Boston, New York, Chicago, Montreal—saying fond good-byes to their groupmates and taking whatever they had learned back home. At Kresge, however, participants remained right there. The result was the emergence of a close-knit community where the traditional academic barrier between “living” and “learning” was obliterated.

In 1970 Carl Rogers, the leading clinical psychologist of his time, had called the encounter group “the single most important social invention of the 20th century.” Yet this great social invention flourished for only about two decades. The T-group was doomed by the return of the Puritan influence on our society—an influence entrenched in American culture, one that ebbs and flows but never quits. When I was at Harvard I had thought that Tim Leary and Dick Alpert’s glowing hope for the power of psilocybin to empty our prisons was naive, but I also found their optimism thrilling and contagious. I was excited by the decade of antiwar protests and movements for equality and the rosy future these events presaged. And I loved the work we were doing in encounter groups, promoting the notions that barriers between people could be lowered, that warmth and understanding could overcome suspicion and prejudice. My own naïveté rested on the assumption that progress toward these goals would be linear. “If things are this good now,” I thought, “just imagine how they will be in ten years!”

What I did not anticipate was that many people outside the college would come to view the goings-on at Kresge with suspicion, others with envy, and a good number with outright hostility. “Hey! Those people are having fun over there! If it’s that much fun, it can’t be educational!” Once, one of our students told a professor that he was headed over to Kresge for an appointment with Michael Kahn, and the professor said, in all seriousness, “Be careful—he might hug you.” It was easy to lampoon T-groups as being nests of touchy-feely self-absorption and pseudopsychology. The campus had a new chancellor and Kresge had a new provost; neither supported the living-learning experiment. The younger faculty members, sensing the opposition of the administration and wider community, were reluctant to participate. Thus, within three years of my arrival at Kresge, the living-learning community collapsed, a harbinger of the demise of T-groups across the country. The students were disappointed. I was heartbroken.

Lecturing, 1994 (top).

Budding social psychologist Josh and his first mentor at their favorite coffeehouse, 1989.

When we moved to Santa Cruz from Texas, I felt I was in paradise. The weather was heavenly. I was near an ocean again. And I was at a liberal institution with a liberal student body. As a place to live, Santa Cruz was everything Vera and I had hoped it would be for ourselves and our family, then and now; three of our four children still live in or near Santa Cruz. At the university the highs were higher than at any place I had ever taught; however, the lows were also lower.

During my first three years on campus, my office was next to a philosopher on one side and a physicist on the other; across the corridor was a historian, and two doors down, a poet. One result of this happy proximity was that the philosopher next door to me, Ellen Suckiel, and I developed a course we called Philosophical and Psychological Foundations of the Life Cycle that, year after year, received the highest student evaluations on campus. In practice the college system at UCSC was a wonderful way to teach undergraduates because it combined the best aspects of a small private college, like Swarthmore or Reed, with the facilities of a large state university. Hal blossomed there; his excitement (and mine) inspired Neal, Julie, and Josh to follow him to UCSC.

Initially, the living-learning community at Kresge College worked beautifully. As in all of the colleges, students could take standard university courses in traditional subjects, such as history, psychology, or biology, as well as special interdisciplinary seminars. At Kresge the seminars added a level of intensity to the usual academic discussion, because they were often run as T-groups. The students were required to learn the course material, and professors retained their authority to make intellectual demands, set requirements, and evaluate the students’ performance. But students also learned about themselves, their relationship to their peers, and ways to communicate clearly and effectively. The T-groups I had been conducting in Bethel, Maine, had a finite duration, about two weeks, and when they were over, participants dispersed to their home cities—Boston, New York, Chicago, Montreal—saying fond good-byes to their groupmates and taking whatever they had learned back home. At Kresge, however, participants remained right there. The result was the emergence of a close-knit community where the traditional academic barrier between “living” and “learning” was obliterated.

In 1970 Carl Rogers, the leading clinical psychologist of his time, had called the encounter group “the single most important social invention of the 20th century.” Yet this great social invention flourished for only about two decades. The T-group was doomed by the return of the Puritan influence on our society—an influence entrenched in American culture, one that ebbs and flows but never quits. When I was at Harvard I had thought that Tim Leary and Dick Alpert’s glowing hope for the power of psilocybin to empty our prisons was naive, but I also found their optimism thrilling and contagious. I was excited by the decade of antiwar protests and movements for equality and the rosy future these events presaged. And I loved the work we were doing in encounter groups, promoting the notions that barriers between people could be lowered, that warmth and understanding could overcome suspicion and prejudice. My own naïveté rested on the assumption that progress toward these goals would be linear. “If things are this good now,” I thought, “just imagine how they will be in ten years!”

What I did not anticipate was that many people outside the college would come to view the goings-on at Kresge with suspicion, others with envy, and a good number with outright hostility. “Hey! Those people are having fun over there! If it’s that much fun, it can’t be educational!” Once, one of our students told a professor that he was headed over to Kresge for an appointment with Michael Kahn, and the professor said, in all seriousness, “Be careful—he might hug you.” It was easy to lampoon T-groups as being nests of touchy-feely self-absorption and pseudopsychology. The campus had a new chancellor and Kresge had a new provost; neither supported the living-learning experiment. The younger faculty members, sensing the opposition of the administration and wider community, were reluctant to participate. Thus, within three years of my arrival at Kresge, the living-learning community collapsed, a harbinger of the demise of T-groups across the country. The students were disappointed. I was heartbroken.