CHAPTER TEN

The Roller Coaster

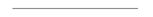

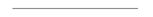

Elliot and Vera hiking in Yosemite, 2005.

One morning in the autumn of 2000, I woke up, and the world looked fuzzy. I thought old age had finally caught up with me and I might need my first pair of glasses, so I went to an ophthalmologist. After dilating my pupils, he peered into my retina, sighed, and shook his head gravely. “I’m afraid that glasses won’t help you,” he said. He sent me to a specialist who informed me that I had a rare kind of macular degeneration and that it was untreatable. He added that I might lose all of my central vision, but if I were lucky the deterioration might stop short of that.

For the next four years, every few months I experienced a sharp decline in my vision. With each decline, I felt an onslaught of dizziness and a loss of control as I bumped into furniture, tripped over minor cracks in the sidewalk, and could barely read. But with a great deal of effort, I would adjust. I would walk more slowly, pay more attention, enlarge the font on my computer, and get used to a world that increasingly looked like a fuzzy version of an impressionist painting on a foggy day.

And I would say, “Hey, I can handle this. If only my eyesight doesn’t get any worse than this, I will be okay.” Then, a few months later, my vision would undergo another sharp decline. Again I would gradually adjust, enlarging the font on my computer to the size of the E on an optometrist’s chart, practicing with a cane to help me with curbs and avoid obstacles in my path, and looking into new computer technologies to help the blind. Friends and colleagues offered support, advice, and news of any breakthroughs in treatment that they read about, although my kind of macular degeneration was, and still is, untreatable. Finally, in 2004, my eyesight hit rock bottom. I lost my central vision completely. The good news is that it won’t get any worse than this; the bad news is that it can’t get any worse than this.

At first I was devastated by the horror of living in a dark and distorted world. My first important decision was what to do about Stanford. As my vision was declining, I had been rewriting my lecture notes, printing them by hand in block letters of ever-increasing size. But when my vision bottomed out, I could no longer read any of them, let alone see my students’ faces and gauge their reactions. During that time of despair, believing there was no way that I could ever teach according to my own standards, I resigned. I realize now that this was an impetuous decision; in the years since then I have gradually trained myself to lecture without notes.

I can still see a little with my peripheral vision, but I can’t recognize faces at a distance greater than ten inches. I need to move very close to someone to know who it is I’m talking to, and this occasionally causes a faux pas: Thinking it’s a friend, I will suddenly find myself standing practically nose to nose with a stranger, and we both quickly pull back in amused embarrassment. This inability to differentiate people, though, is hardest on me when my four adorable little granddaughters are visiting; I often have difficulty telling them apart—a realization that never fails to break my heart. Because of experiences like these and the anxiety of being in bustling, unfamiliar environments, my blindness seems to have rekindled my childhood shyness, something that I thought I had succeeded in squelching in adulthood.

I used to think of blindness as simply a severe diminution of eyesight, but it is much more than that. I not only can’t see things that are there but frequently see things that aren’t there. For a few years I would see Hebrew words as if they were printed on a wall in front of me, not the usual kind as in a prayer book, but the ornate kind that appear in the Torah, beautifully hand-lettered works of art. (Of these, the most memorable to me was the Hebrew word timshel, which means “thou mayest.”) Still today, every two or three minutes, a powerful burst of light goes off somewhere behind my eyes. These disconcerting visual auras have required imaginative coping skills. At first I tried poking fun at myself by pretending that I was being surrounded by paparazzi—hence all the flashbulbs. Now I just live with them.

If I learned anything from my older brother, Jason, it is the absolute refusal to complain about the hand I’ve been dealt, but to play the cards as well as I can. I have been trying to do this without resorting to denial at one extreme or wallowing in self-pity at the other. It certainly is no laughing matter for a “shy person” like me to be lost in airports or in unfamiliar cities, being forced to approach strangers and ask for directions. It is no joke for a scholar to be unable to skim a journal article to see if it contains anything of interest. But humor, combined with a little dissonance reduction, has carried me through the most difficult moments. There’s an old Jewish joke that captures my feeling:

Two old friends meet on the street. “Nu, Jake,” says Sol. “How are you feeling now that you have arthritis and cancer?”

“Terrible. But not so bad.”

With every decrement in my eyesight, part of my adjustment has involved minimizing the importance of the things I can no longer do (who likes cocktail parties and journal articles, anyway?) and focusing on the things that I can do, like conversing with my friends and immersing myself in audiobooks. It is becoming easier for this shy person to ask strangers on the street for help, because I have learned that most people will respond with patience and kindness. If I can no longer catch a baseball, or even see one, I still can run—as long as I do it on the beach at the water’s edge, early in the morning, when there are fewer toddlers to trip over.

Elliot and Vera hiking in Yosemite, 2005.

One morning in the autumn of 2000, I woke up, and the world looked fuzzy. I thought old age had finally caught up with me and I might need my first pair of glasses, so I went to an ophthalmologist. After dilating my pupils, he peered into my retina, sighed, and shook his head gravely. “I’m afraid that glasses won’t help you,” he said. He sent me to a specialist who informed me that I had a rare kind of macular degeneration and that it was untreatable. He added that I might lose all of my central vision, but if I were lucky the deterioration might stop short of that.

For the next four years, every few months I experienced a sharp decline in my vision. With each decline, I felt an onslaught of dizziness and a loss of control as I bumped into furniture, tripped over minor cracks in the sidewalk, and could barely read. But with a great deal of effort, I would adjust. I would walk more slowly, pay more attention, enlarge the font on my computer, and get used to a world that increasingly looked like a fuzzy version of an impressionist painting on a foggy day.

And I would say, “Hey, I can handle this. If only my eyesight doesn’t get any worse than this, I will be okay.” Then, a few months later, my vision would undergo another sharp decline. Again I would gradually adjust, enlarging the font on my computer to the size of the E on an optometrist’s chart, practicing with a cane to help me with curbs and avoid obstacles in my path, and looking into new computer technologies to help the blind. Friends and colleagues offered support, advice, and news of any breakthroughs in treatment that they read about, although my kind of macular degeneration was, and still is, untreatable. Finally, in 2004, my eyesight hit rock bottom. I lost my central vision completely. The good news is that it won’t get any worse than this; the bad news is that it can’t get any worse than this.

At first I was devastated by the horror of living in a dark and distorted world. My first important decision was what to do about Stanford. As my vision was declining, I had been rewriting my lecture notes, printing them by hand in block letters of ever-increasing size. But when my vision bottomed out, I could no longer read any of them, let alone see my students’ faces and gauge their reactions. During that time of despair, believing there was no way that I could ever teach according to my own standards, I resigned. I realize now that this was an impetuous decision; in the years since then I have gradually trained myself to lecture without notes.

I can still see a little with my peripheral vision, but I can’t recognize faces at a distance greater than ten inches. I need to move very close to someone to know who it is I’m talking to, and this occasionally causes a faux pas: Thinking it’s a friend, I will suddenly find myself standing practically nose to nose with a stranger, and we both quickly pull back in amused embarrassment. This inability to differentiate people, though, is hardest on me when my four adorable little granddaughters are visiting; I often have difficulty telling them apart—a realization that never fails to break my heart. Because of experiences like these and the anxiety of being in bustling, unfamiliar environments, my blindness seems to have rekindled my childhood shyness, something that I thought I had succeeded in squelching in adulthood.

I used to think of blindness as simply a severe diminution of eyesight, but it is much more than that. I not only can’t see things that are there but frequently see things that aren’t there. For a few years I would see Hebrew words as if they were printed on a wall in front of me, not the usual kind as in a prayer book, but the ornate kind that appear in the Torah, beautifully hand-lettered works of art. (Of these, the most memorable to me was the Hebrew word timshel, which means “thou mayest.”) Still today, every two or three minutes, a powerful burst of light goes off somewhere behind my eyes. These disconcerting visual auras have required imaginative coping skills. At first I tried poking fun at myself by pretending that I was being surrounded by paparazzi—hence all the flashbulbs. Now I just live with them.

If I learned anything from my older brother, Jason, it is the absolute refusal to complain about the hand I’ve been dealt, but to play the cards as well as I can. I have been trying to do this without resorting to denial at one extreme or wallowing in self-pity at the other. It certainly is no laughing matter for a “shy person” like me to be lost in airports or in unfamiliar cities, being forced to approach strangers and ask for directions. It is no joke for a scholar to be unable to skim a journal article to see if it contains anything of interest. But humor, combined with a little dissonance reduction, has carried me through the most difficult moments. There’s an old Jewish joke that captures my feeling:

Two old friends meet on the street. “Nu, Jake,” says Sol. “How are you feeling now that you have arthritis and cancer?”

“Terrible. But not so bad.”

With every decrement in my eyesight, part of my adjustment has involved minimizing the importance of the things I can no longer do (who likes cocktail parties and journal articles, anyway?) and focusing on the things that I can do, like conversing with my friends and immersing myself in audiobooks. It is becoming easier for this shy person to ask strangers on the street for help, because I have learned that most people will respond with patience and kindness. If I can no longer catch a baseball, or even see one, I still can run—as long as I do it on the beach at the water’s edge, early in the morning, when there are fewer toddlers to trip over.

One of the primary reasons I retired was to do more writing for the general public, and indeed I did—until my inability to read and edit my work made writing by myself extremely tedious. (Where do I put the fucking cursor?) In the past, I had enjoyed writing with colleagues, but now my inability to read forced the collaboration to take new and richer forms. Collaboration is about listening. My coauthors and I begin by talking out our ideas, arguments, and rebuttals. Once we have a first draft, my coauthor reads it aloud. The back-and-forth of the spoken word not only intensifies the exchange of ideas but also enhances the use of language: It is easier to spot clunkers by hearing them than by seeing them on a page. (In fact, I now recommend that all writers listen to their words as well as read them; you don’t have to be blind to do that.) Using this process I have collaborated with two of my sons, Hal and Josh, in three revisions of The Social Animal.

After I went blind the first book I attempted from scratch, Mistakes Were Made (but Not by Me), was written with my friend and colleague Carol Tavris. Even Carol, who is one of psychology’s most gifted writers, was surprised and delighted at how much the oral back-and-forth improved the final product. This book has a special poignancy for me, because it reflects another kind of full-circle experience: It is an homage to my close friend and mentor Leon Festinger. In 1957, under duress, I had read A Theory of Cognitive Dissonance in manuscript form, and it changed my life. Leon was a great scientist but utterly uninterested in applying his science to better the human condition. In Mistakes Were Made, we showed how dissonance theory can explain why so many people can do harmful, foolish, self-defeating, or cruel things and still sleep soundly at night. Leon would not have cared about explaining why so many prosecutors won’t accept DNA evidence showing that they put the wrong guy in prison, why some therapists justify the use of outdated methods that are harming their clients, why most scientists who accept money from industry convince themselves that they can’t possibly be influenced by it, and why so many quarreling couples (and nations) cannot see the other’s perspective. But I had always felt that dissonance theory was too powerful to leave in a laboratory, and so, in a sense, Carol and I dragged Leon, kicking and screaming, into the real world. Our book was published in 2007, exactly fifty years after the publication of A Theory of Cognitive Dissonance.

One of the primary reasons I retired was to do more writing for the general public, and indeed I did—until my inability to read and edit my work made writing by myself extremely tedious. (Where do I put the fucking cursor?) In the past, I had enjoyed writing with colleagues, but now my inability to read forced the collaboration to take new and richer forms. Collaboration is about listening. My coauthors and I begin by talking out our ideas, arguments, and rebuttals. Once we have a first draft, my coauthor reads it aloud. The back-and-forth of the spoken word not only intensifies the exchange of ideas but also enhances the use of language: It is easier to spot clunkers by hearing them than by seeing them on a page. (In fact, I now recommend that all writers listen to their words as well as read them; you don’t have to be blind to do that.) Using this process I have collaborated with two of my sons, Hal and Josh, in three revisions of The Social Animal.

After I went blind the first book I attempted from scratch, Mistakes Were Made (but Not by Me), was written with my friend and colleague Carol Tavris. Even Carol, who is one of psychology’s most gifted writers, was surprised and delighted at how much the oral back-and-forth improved the final product. This book has a special poignancy for me, because it reflects another kind of full-circle experience: It is an homage to my close friend and mentor Leon Festinger. In 1957, under duress, I had read A Theory of Cognitive Dissonance in manuscript form, and it changed my life. Leon was a great scientist but utterly uninterested in applying his science to better the human condition. In Mistakes Were Made, we showed how dissonance theory can explain why so many people can do harmful, foolish, self-defeating, or cruel things and still sleep soundly at night. Leon would not have cared about explaining why so many prosecutors won’t accept DNA evidence showing that they put the wrong guy in prison, why some therapists justify the use of outdated methods that are harming their clients, why most scientists who accept money from industry convince themselves that they can’t possibly be influenced by it, and why so many quarreling couples (and nations) cannot see the other’s perspective. But I had always felt that dissonance theory was too powerful to leave in a laboratory, and so, in a sense, Carol and I dragged Leon, kicking and screaming, into the real world. Our book was published in 2007, exactly fifty years after the publication of A Theory of Cognitive Dissonance.

Today I realize that it is only my eyesight I have lost, not my vision. The first person to teach me this valuable lesson was my granddaughter Ruth, who was six years old in 2003, when my eyesight was almost completely gone. Although she is uncommonly bright, she was having difficulty learning how to read. She could not get the hang of it, and as the end of the school year approached, her teacher indicated that if she couldn’t read, she would have to repeat the first grade. How could I help her grasp the essentials of reading, when I myself was nearly blind? The obvious hook was storytelling. Ruth was always begging me to tell her stories, stories I made up as I went along, so that I almost never told the same story more than once. The next time she asked for one, I suggested that we compose it together. She was excited by the idea. Then I said, “I have a terrible memory. As we go along, I had better write it down, so that if we are interrupted, we won’t forget where we left off.” I pulled out a stack of five-by-seven-inch cards, and as we composed, I carefully printed our words on the cards. It was hard for me to see, of course, so I needed to print in large, bold letters, only four or five words to a card. There we were, one of us not knowing how to read, the other barely able to decipher even oversized words.

Ruth asked if the story could be about me when I was a little boy, and she also insisted that she be one of the central characters. “How can you be a character in a story that happened before you were born?” I asked.

“C’mon, Grandpa, you can make something up.” She was right, of course; I was thinking linearly. And so began The Adventures of Ruthie and a Little Boy Named Grandpa. Our story was an inside-out combination of Hansel and Gretel and Jack and the Beanstalk, where the old woman and the giant from the traditional fairy tales turn out to be nice people. Little Grandpa, because he is vaguely aware of the original stories, is suspicious and hesitant, while Ruth is trusting and adventurous.

After we had filled several cards, I told Ruth that I wanted to check how we had described the old woman. “Please shuffle through the cards to look for when the old woman makes her first appearance,” I said. “Here is how you find the card with the old woman on it. The O sound in ‘old’ is a circle, so look for a word that starts with a circle.” She found it. Then, a few minutes later, I would ask her to find the card with the word “oven” on it. I said, “It starts with the same circle, but then it has a V sound after the O; the V looks like an arrowhead pointed downward.” Because we were engaged in a project that was of great interest to her, and because there was no pressure, Ruth was motivated to look for letters that previously had been meaningless and confusing. Within a few days, she was reading whole sentences. Within a month, there was no stopping her. She was reading everything in sight. Of course, she would have learned to read eventually without my help. Nonetheless, because it was such an exhilarating week for Ruthie and me, although for different reasons, I arranged for the story to be published by a vanity press, with the two of us as coauthors. That little book is a sweet reminder of one of my favorite teaching experiences.

It is not by accident that I lived near enough to my grandchildren to have developed such close relationships with them. When I reflect on my life, I see with the clarity of hindsight the intersecting strands of chance and intention that made our family as tight as it is. Our decision to move to Santa Cruz was based on the conscious reasoning that if the locale was attractive enough, our children would want to establish their own lives near us. But it was by chance that at the particular moment that Vera and I had decided to leave Texas, UCSC was looking for a professor with my combination of skills and experience. Today, so many years later, Hal, Neal, and Julie still live in or near this city with their spouses and children; Josh and his family visit at every opportunity.

Was it due to chance that we lost none of our children to the siren song of drugs and rebellion that claimed so many of their generation, or was it due to our child-rearing style, which can best be termed “vigilant laissez-faire”? Vera and I can’t be sure. We tried hard to avoid meddling in their private lives while encouraging them to talk to us about anything and everything that concerned them. Even so, they kept many of their adventures, misadventures, explorations, and heartbreaks to themselves, telling us about them only years later. For example, we informed all our kids that when the bedroom door was locked, we were not to be disturbed—unless, of course, they needed us to drive them to the emergency room. In her thirties, Julie told us, with amusement, “When I was three years old, I sat outside your bedroom door for an hour, hoping you would hear me whimpering!” More seriously, Josh recently let us know that he had been picked on for a whole year by his fourth-grade teacher. “I wish you had known about it,” he complained. Perhaps we should have been a little more vigilant and a little less laissez-faire. But all of our children somehow found their own way, forgiving us our mistakes and oversights, remaining close to us and to one another.

In adulthood, each of our children chose to do the kind of work that reflects his or her individual interest and proclivity. But their choices share an underlying belief that serving the common good is what it means to live the good life. Hal became an environmental sociologist and expert on solar energy; he is training minority teenagers, unemployed contractors, and autoworkers to become proficient in a technology that has a bright present and an even brighter future. Neal became a firefighter, a first responder in rescuing people from burning buildings, automobile accidents, and the devastation of earthquakes. Julie became an educational consultant, nurturing and evaluating innovative strategies adopted by primary and secondary schools. Joshua became a professor of social psychology. When I think of how many things come around again in our lives, I smile as I recall the Jensen episode at UCSC, years before Josh arrived as a student. Today, Josh’s innovative research on developing interventions that raise the motivation and test scores of the most disadvantaged minorities is a far more effective riposte to Jensen’s misguided ideas than I (or anyone else) could have come up with at the time.

Today I realize that it is only my eyesight I have lost, not my vision. The first person to teach me this valuable lesson was my granddaughter Ruth, who was six years old in 2003, when my eyesight was almost completely gone. Although she is uncommonly bright, she was having difficulty learning how to read. She could not get the hang of it, and as the end of the school year approached, her teacher indicated that if she couldn’t read, she would have to repeat the first grade. How could I help her grasp the essentials of reading, when I myself was nearly blind? The obvious hook was storytelling. Ruth was always begging me to tell her stories, stories I made up as I went along, so that I almost never told the same story more than once. The next time she asked for one, I suggested that we compose it together. She was excited by the idea. Then I said, “I have a terrible memory. As we go along, I had better write it down, so that if we are interrupted, we won’t forget where we left off.” I pulled out a stack of five-by-seven-inch cards, and as we composed, I carefully printed our words on the cards. It was hard for me to see, of course, so I needed to print in large, bold letters, only four or five words to a card. There we were, one of us not knowing how to read, the other barely able to decipher even oversized words.

Ruth asked if the story could be about me when I was a little boy, and she also insisted that she be one of the central characters. “How can you be a character in a story that happened before you were born?” I asked.

“C’mon, Grandpa, you can make something up.” She was right, of course; I was thinking linearly. And so began The Adventures of Ruthie and a Little Boy Named Grandpa. Our story was an inside-out combination of Hansel and Gretel and Jack and the Beanstalk, where the old woman and the giant from the traditional fairy tales turn out to be nice people. Little Grandpa, because he is vaguely aware of the original stories, is suspicious and hesitant, while Ruth is trusting and adventurous.

After we had filled several cards, I told Ruth that I wanted to check how we had described the old woman. “Please shuffle through the cards to look for when the old woman makes her first appearance,” I said. “Here is how you find the card with the old woman on it. The O sound in ‘old’ is a circle, so look for a word that starts with a circle.” She found it. Then, a few minutes later, I would ask her to find the card with the word “oven” on it. I said, “It starts with the same circle, but then it has a V sound after the O; the V looks like an arrowhead pointed downward.” Because we were engaged in a project that was of great interest to her, and because there was no pressure, Ruth was motivated to look for letters that previously had been meaningless and confusing. Within a few days, she was reading whole sentences. Within a month, there was no stopping her. She was reading everything in sight. Of course, she would have learned to read eventually without my help. Nonetheless, because it was such an exhilarating week for Ruthie and me, although for different reasons, I arranged for the story to be published by a vanity press, with the two of us as coauthors. That little book is a sweet reminder of one of my favorite teaching experiences.

It is not by accident that I lived near enough to my grandchildren to have developed such close relationships with them. When I reflect on my life, I see with the clarity of hindsight the intersecting strands of chance and intention that made our family as tight as it is. Our decision to move to Santa Cruz was based on the conscious reasoning that if the locale was attractive enough, our children would want to establish their own lives near us. But it was by chance that at the particular moment that Vera and I had decided to leave Texas, UCSC was looking for a professor with my combination of skills and experience. Today, so many years later, Hal, Neal, and Julie still live in or near this city with their spouses and children; Josh and his family visit at every opportunity.

Was it due to chance that we lost none of our children to the siren song of drugs and rebellion that claimed so many of their generation, or was it due to our child-rearing style, which can best be termed “vigilant laissez-faire”? Vera and I can’t be sure. We tried hard to avoid meddling in their private lives while encouraging them to talk to us about anything and everything that concerned them. Even so, they kept many of their adventures, misadventures, explorations, and heartbreaks to themselves, telling us about them only years later. For example, we informed all our kids that when the bedroom door was locked, we were not to be disturbed—unless, of course, they needed us to drive them to the emergency room. In her thirties, Julie told us, with amusement, “When I was three years old, I sat outside your bedroom door for an hour, hoping you would hear me whimpering!” More seriously, Josh recently let us know that he had been picked on for a whole year by his fourth-grade teacher. “I wish you had known about it,” he complained. Perhaps we should have been a little more vigilant and a little less laissez-faire. But all of our children somehow found their own way, forgiving us our mistakes and oversights, remaining close to us and to one another.

In adulthood, each of our children chose to do the kind of work that reflects his or her individual interest and proclivity. But their choices share an underlying belief that serving the common good is what it means to live the good life. Hal became an environmental sociologist and expert on solar energy; he is training minority teenagers, unemployed contractors, and autoworkers to become proficient in a technology that has a bright present and an even brighter future. Neal became a firefighter, a first responder in rescuing people from burning buildings, automobile accidents, and the devastation of earthquakes. Julie became an educational consultant, nurturing and evaluating innovative strategies adopted by primary and secondary schools. Joshua became a professor of social psychology. When I think of how many things come around again in our lives, I smile as I recall the Jensen episode at UCSC, years before Josh arrived as a student. Today, Josh’s innovative research on developing interventions that raise the motivation and test scores of the most disadvantaged minorities is a far more effective riposte to Jensen’s misguided ideas than I (or anyone else) could have come up with at the time.

A few years ago Vera and I managed to make contact with our old friend Dick Alpert. Dick had suffered a serious stroke that left him slow of speech and partially paralyzed. We met in a restaurant, he in a wheelchair and I walking hesitantly with a white cane. The waiters—perhaps out of curiosity about what an old blind guy and an old cripple had to say to each other, perhaps because they recognized Baba Ram Dass—hovered near our table, surreptitiously eavesdropping. We spoke of the many ways in which our lives had intersected, of religious belief (his) and skepticism (mine), and of his transformation from developmental psychologist to spiritual leader. Near the end of our meeting, he asked me kindly, “And you, Ellie? Are you going to end up as a social psychologist?” Without a moment’s hesitation I said, “I don’t intend to end up at all!” His face lit up, and with great effort he reached for my hand. I thought he wanted to shake it, but instead he brought my hand to his lips and kissed it.

Vera and I walked outside the restaurant and watched Dick’s driver wheel him up a ramp and into the van. He looked frail and helpless, yet he was still the same bright, charming, charismatic guy I had known for most of my life. I admired the courage with which he was dealing with the debilitating effects of his stroke. Life is a roller coaster, I thought.

A few years ago Vera and I managed to make contact with our old friend Dick Alpert. Dick had suffered a serious stroke that left him slow of speech and partially paralyzed. We met in a restaurant, he in a wheelchair and I walking hesitantly with a white cane. The waiters—perhaps out of curiosity about what an old blind guy and an old cripple had to say to each other, perhaps because they recognized Baba Ram Dass—hovered near our table, surreptitiously eavesdropping. We spoke of the many ways in which our lives had intersected, of religious belief (his) and skepticism (mine), and of his transformation from developmental psychologist to spiritual leader. Near the end of our meeting, he asked me kindly, “And you, Ellie? Are you going to end up as a social psychologist?” Without a moment’s hesitation I said, “I don’t intend to end up at all!” His face lit up, and with great effort he reached for my hand. I thought he wanted to shake it, but instead he brought my hand to his lips and kissed it.

Vera and I walked outside the restaurant and watched Dick’s driver wheel him up a ramp and into the van. He looked frail and helpless, yet he was still the same bright, charming, charismatic guy I had known for most of my life. I admired the courage with which he was dealing with the debilitating effects of his stroke. Life is a roller coaster, I thought.

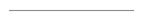

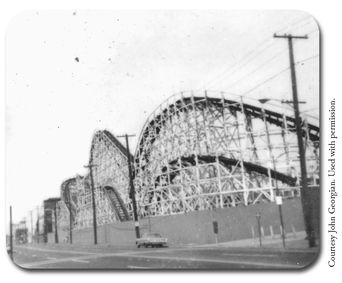

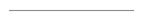

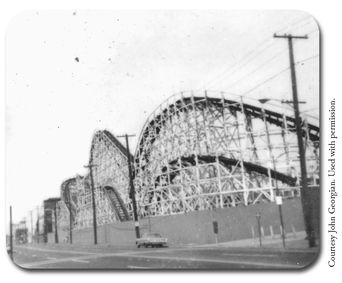

When I was twelve years old, Jason took me for my first ride on the roller coaster at Revere Beach. Although I had been nagging him to take me for more than a year, as the ride started, I was plenty scared. Jason, who was a veteran of thirty-odd roller-coaster rides, assured me that I had nothing to be afraid of. As usual, he was right; it was an exhilarating experience. When it was over I asked him, “What’s your favorite part of the ride?”

“What’s your favorite part?” he asked.

“I hate when you do that!” I said.

He smiled and said, “Do what?”

“I hate when you do that, too!” I shouted.

I was so annoyed at him I decided to give him the old silent treatment. But I was so eager to discuss the experience that the silent treatment lasted about thirty-four seconds. I said, “My favorite part was right after we went flying down that steep drop and we suddenly curved up again. It was so exciting I could feel my heart go right up into my throat.”

“Yeah. I know what you mean,” he said. “That used to be my favorite part, too. But you know what? After a few rides, it dawned on me that I wasn’t enjoying the rest of the experience because I kept waiting for that part of the ride to show up. So then I played a trick on myself. I pretended that my favorite part was when we were just starting down that steep hill. But then I found myself waiting for that to occur and missing out on the enjoyment of the rest of the ride. So then I pushed it back another notch and pretended to myself that my favorite part was when we were climbing the hill . . . and then it dawned on me that it’s stupid to have a favorite part. Because it’s all the roller coaster—the ups, the downs, the climbing, the falling, the gradual turns, the sharp twists. It’s all the roller coaster.”

My brother was only fourteen when he said that. Although he may not have been fully aware of it, I can see, looking at it now, he might have been using the roller coaster as a metaphor for living.

What’s my favorite part of this roller coaster I’ve been riding for seventy-eight years? As my fourteen-year-old mentor taught me, there is no favorite part. Another way of putting it is that it is all my favorite part. All of it—the plummets of blindness and loss, as well as the exhilaration that comes from giving a compelling lecture or making an important scientific discovery, and the warmth that comes from loving and being loved by my wife, kids, grandchildren, and friends. Indeed, if I were forced to choose one favorite part, I would say right now, but I guess I could have said that anywhere along the way.

When I was twelve years old, Jason took me for my first ride on the roller coaster at Revere Beach. Although I had been nagging him to take me for more than a year, as the ride started, I was plenty scared. Jason, who was a veteran of thirty-odd roller-coaster rides, assured me that I had nothing to be afraid of. As usual, he was right; it was an exhilarating experience. When it was over I asked him, “What’s your favorite part of the ride?”

“What’s your favorite part?” he asked.

“I hate when you do that!” I said.

He smiled and said, “Do what?”

“I hate when you do that, too!” I shouted.

I was so annoyed at him I decided to give him the old silent treatment. But I was so eager to discuss the experience that the silent treatment lasted about thirty-four seconds. I said, “My favorite part was right after we went flying down that steep drop and we suddenly curved up again. It was so exciting I could feel my heart go right up into my throat.”

“Yeah. I know what you mean,” he said. “That used to be my favorite part, too. But you know what? After a few rides, it dawned on me that I wasn’t enjoying the rest of the experience because I kept waiting for that part of the ride to show up. So then I played a trick on myself. I pretended that my favorite part was when we were just starting down that steep hill. But then I found myself waiting for that to occur and missing out on the enjoyment of the rest of the ride. So then I pushed it back another notch and pretended to myself that my favorite part was when we were climbing the hill . . . and then it dawned on me that it’s stupid to have a favorite part. Because it’s all the roller coaster—the ups, the downs, the climbing, the falling, the gradual turns, the sharp twists. It’s all the roller coaster.”

My brother was only fourteen when he said that. Although he may not have been fully aware of it, I can see, looking at it now, he might have been using the roller coaster as a metaphor for living.

What’s my favorite part of this roller coaster I’ve been riding for seventy-eight years? As my fourteen-year-old mentor taught me, there is no favorite part. Another way of putting it is that it is all my favorite part. All of it—the plummets of blindness and loss, as well as the exhilaration that comes from giving a compelling lecture or making an important scientific discovery, and the warmth that comes from loving and being loved by my wife, kids, grandchildren, and friends. Indeed, if I were forced to choose one favorite part, I would say right now, but I guess I could have said that anywhere along the way.

在线阅读网免费看书:http://www.yuedU88.cOm/

在线阅读网免费看书:http://www.yuedU88.cOm/

Elliot and Vera hiking in Yosemite, 2005.

One morning in the autumn of 2000, I woke up, and the world looked fuzzy. I thought old age had finally caught up with me and I might need my first pair of glasses, so I went to an ophthalmologist. After dilating my pupils, he peered into my retina, sighed, and shook his head gravely. “I’m afraid that glasses won’t help you,” he said. He sent me to a specialist who informed me that I had a rare kind of macular degeneration and that it was untreatable. He added that I might lose all of my central vision, but if I were lucky the deterioration might stop short of that.

For the next four years, every few months I experienced a sharp decline in my vision. With each decline, I felt an onslaught of dizziness and a loss of control as I bumped into furniture, tripped over minor cracks in the sidewalk, and could barely read. But with a great deal of effort, I would adjust. I would walk more slowly, pay more attention, enlarge the font on my computer, and get used to a world that increasingly looked like a fuzzy version of an impressionist painting on a foggy day.

And I would say, “Hey, I can handle this. If only my eyesight doesn’t get any worse than this, I will be okay.” Then, a few months later, my vision would undergo another sharp decline. Again I would gradually adjust, enlarging the font on my computer to the size of the E on an optometrist’s chart, practicing with a cane to help me with curbs and avoid obstacles in my path, and looking into new computer technologies to help the blind. Friends and colleagues offered support, advice, and news of any breakthroughs in treatment that they read about, although my kind of macular degeneration was, and still is, untreatable. Finally, in 2004, my eyesight hit rock bottom. I lost my central vision completely. The good news is that it won’t get any worse than this; the bad news is that it can’t get any worse than this.

At first I was devastated by the horror of living in a dark and distorted world. My first important decision was what to do about Stanford. As my vision was declining, I had been rewriting my lecture notes, printing them by hand in block letters of ever-increasing size. But when my vision bottomed out, I could no longer read any of them, let alone see my students’ faces and gauge their reactions. During that time of despair, believing there was no way that I could ever teach according to my own standards, I resigned. I realize now that this was an impetuous decision; in the years since then I have gradually trained myself to lecture without notes.

I can still see a little with my peripheral vision, but I can’t recognize faces at a distance greater than ten inches. I need to move very close to someone to know who it is I’m talking to, and this occasionally causes a faux pas: Thinking it’s a friend, I will suddenly find myself standing practically nose to nose with a stranger, and we both quickly pull back in amused embarrassment. This inability to differentiate people, though, is hardest on me when my four adorable little granddaughters are visiting; I often have difficulty telling them apart—a realization that never fails to break my heart. Because of experiences like these and the anxiety of being in bustling, unfamiliar environments, my blindness seems to have rekindled my childhood shyness, something that I thought I had succeeded in squelching in adulthood.

I used to think of blindness as simply a severe diminution of eyesight, but it is much more than that. I not only can’t see things that are there but frequently see things that aren’t there. For a few years I would see Hebrew words as if they were printed on a wall in front of me, not the usual kind as in a prayer book, but the ornate kind that appear in the Torah, beautifully hand-lettered works of art. (Of these, the most memorable to me was the Hebrew word timshel, which means “thou mayest.”) Still today, every two or three minutes, a powerful burst of light goes off somewhere behind my eyes. These disconcerting visual auras have required imaginative coping skills. At first I tried poking fun at myself by pretending that I was being surrounded by paparazzi—hence all the flashbulbs. Now I just live with them.

If I learned anything from my older brother, Jason, it is the absolute refusal to complain about the hand I’ve been dealt, but to play the cards as well as I can. I have been trying to do this without resorting to denial at one extreme or wallowing in self-pity at the other. It certainly is no laughing matter for a “shy person” like me to be lost in airports or in unfamiliar cities, being forced to approach strangers and ask for directions. It is no joke for a scholar to be unable to skim a journal article to see if it contains anything of interest. But humor, combined with a little dissonance reduction, has carried me through the most difficult moments. There’s an old Jewish joke that captures my feeling:

Two old friends meet on the street. “Nu, Jake,” says Sol. “How are you feeling now that you have arthritis and cancer?”

“Terrible. But not so bad.”

With every decrement in my eyesight, part of my adjustment has involved minimizing the importance of the things I can no longer do (who likes cocktail parties and journal articles, anyway?) and focusing on the things that I can do, like conversing with my friends and immersing myself in audiobooks. It is becoming easier for this shy person to ask strangers on the street for help, because I have learned that most people will respond with patience and kindness. If I can no longer catch a baseball, or even see one, I still can run—as long as I do it on the beach at the water’s edge, early in the morning, when there are fewer toddlers to trip over.

Elliot and Vera hiking in Yosemite, 2005.

One morning in the autumn of 2000, I woke up, and the world looked fuzzy. I thought old age had finally caught up with me and I might need my first pair of glasses, so I went to an ophthalmologist. After dilating my pupils, he peered into my retina, sighed, and shook his head gravely. “I’m afraid that glasses won’t help you,” he said. He sent me to a specialist who informed me that I had a rare kind of macular degeneration and that it was untreatable. He added that I might lose all of my central vision, but if I were lucky the deterioration might stop short of that.

For the next four years, every few months I experienced a sharp decline in my vision. With each decline, I felt an onslaught of dizziness and a loss of control as I bumped into furniture, tripped over minor cracks in the sidewalk, and could barely read. But with a great deal of effort, I would adjust. I would walk more slowly, pay more attention, enlarge the font on my computer, and get used to a world that increasingly looked like a fuzzy version of an impressionist painting on a foggy day.

And I would say, “Hey, I can handle this. If only my eyesight doesn’t get any worse than this, I will be okay.” Then, a few months later, my vision would undergo another sharp decline. Again I would gradually adjust, enlarging the font on my computer to the size of the E on an optometrist’s chart, practicing with a cane to help me with curbs and avoid obstacles in my path, and looking into new computer technologies to help the blind. Friends and colleagues offered support, advice, and news of any breakthroughs in treatment that they read about, although my kind of macular degeneration was, and still is, untreatable. Finally, in 2004, my eyesight hit rock bottom. I lost my central vision completely. The good news is that it won’t get any worse than this; the bad news is that it can’t get any worse than this.

At first I was devastated by the horror of living in a dark and distorted world. My first important decision was what to do about Stanford. As my vision was declining, I had been rewriting my lecture notes, printing them by hand in block letters of ever-increasing size. But when my vision bottomed out, I could no longer read any of them, let alone see my students’ faces and gauge their reactions. During that time of despair, believing there was no way that I could ever teach according to my own standards, I resigned. I realize now that this was an impetuous decision; in the years since then I have gradually trained myself to lecture without notes.

I can still see a little with my peripheral vision, but I can’t recognize faces at a distance greater than ten inches. I need to move very close to someone to know who it is I’m talking to, and this occasionally causes a faux pas: Thinking it’s a friend, I will suddenly find myself standing practically nose to nose with a stranger, and we both quickly pull back in amused embarrassment. This inability to differentiate people, though, is hardest on me when my four adorable little granddaughters are visiting; I often have difficulty telling them apart—a realization that never fails to break my heart. Because of experiences like these and the anxiety of being in bustling, unfamiliar environments, my blindness seems to have rekindled my childhood shyness, something that I thought I had succeeded in squelching in adulthood.

I used to think of blindness as simply a severe diminution of eyesight, but it is much more than that. I not only can’t see things that are there but frequently see things that aren’t there. For a few years I would see Hebrew words as if they were printed on a wall in front of me, not the usual kind as in a prayer book, but the ornate kind that appear in the Torah, beautifully hand-lettered works of art. (Of these, the most memorable to me was the Hebrew word timshel, which means “thou mayest.”) Still today, every two or three minutes, a powerful burst of light goes off somewhere behind my eyes. These disconcerting visual auras have required imaginative coping skills. At first I tried poking fun at myself by pretending that I was being surrounded by paparazzi—hence all the flashbulbs. Now I just live with them.

If I learned anything from my older brother, Jason, it is the absolute refusal to complain about the hand I’ve been dealt, but to play the cards as well as I can. I have been trying to do this without resorting to denial at one extreme or wallowing in self-pity at the other. It certainly is no laughing matter for a “shy person” like me to be lost in airports or in unfamiliar cities, being forced to approach strangers and ask for directions. It is no joke for a scholar to be unable to skim a journal article to see if it contains anything of interest. But humor, combined with a little dissonance reduction, has carried me through the most difficult moments. There’s an old Jewish joke that captures my feeling:

Two old friends meet on the street. “Nu, Jake,” says Sol. “How are you feeling now that you have arthritis and cancer?”

“Terrible. But not so bad.”

With every decrement in my eyesight, part of my adjustment has involved minimizing the importance of the things I can no longer do (who likes cocktail parties and journal articles, anyway?) and focusing on the things that I can do, like conversing with my friends and immersing myself in audiobooks. It is becoming easier for this shy person to ask strangers on the street for help, because I have learned that most people will respond with patience and kindness. If I can no longer catch a baseball, or even see one, I still can run—as long as I do it on the beach at the water’s edge, early in the morning, when there are fewer toddlers to trip over.

One of the primary reasons I retired was to do more writing for the general public, and indeed I did—until my inability to read and edit my work made writing by myself extremely tedious. (Where do I put the fucking cursor?) In the past, I had enjoyed writing with colleagues, but now my inability to read forced the collaboration to take new and richer forms. Collaboration is about listening. My coauthors and I begin by talking out our ideas, arguments, and rebuttals. Once we have a first draft, my coauthor reads it aloud. The back-and-forth of the spoken word not only intensifies the exchange of ideas but also enhances the use of language: It is easier to spot clunkers by hearing them than by seeing them on a page. (In fact, I now recommend that all writers listen to their words as well as read them; you don’t have to be blind to do that.) Using this process I have collaborated with two of my sons, Hal and Josh, in three revisions of The Social Animal.

After I went blind the first book I attempted from scratch, Mistakes Were Made (but Not by Me), was written with my friend and colleague Carol Tavris. Even Carol, who is one of psychology’s most gifted writers, was surprised and delighted at how much the oral back-and-forth improved the final product. This book has a special poignancy for me, because it reflects another kind of full-circle experience: It is an homage to my close friend and mentor Leon Festinger. In 1957, under duress, I had read A Theory of Cognitive Dissonance in manuscript form, and it changed my life. Leon was a great scientist but utterly uninterested in applying his science to better the human condition. In Mistakes Were Made, we showed how dissonance theory can explain why so many people can do harmful, foolish, self-defeating, or cruel things and still sleep soundly at night. Leon would not have cared about explaining why so many prosecutors won’t accept DNA evidence showing that they put the wrong guy in prison, why some therapists justify the use of outdated methods that are harming their clients, why most scientists who accept money from industry convince themselves that they can’t possibly be influenced by it, and why so many quarreling couples (and nations) cannot see the other’s perspective. But I had always felt that dissonance theory was too powerful to leave in a laboratory, and so, in a sense, Carol and I dragged Leon, kicking and screaming, into the real world. Our book was published in 2007, exactly fifty years after the publication of A Theory of Cognitive Dissonance.

One of the primary reasons I retired was to do more writing for the general public, and indeed I did—until my inability to read and edit my work made writing by myself extremely tedious. (Where do I put the fucking cursor?) In the past, I had enjoyed writing with colleagues, but now my inability to read forced the collaboration to take new and richer forms. Collaboration is about listening. My coauthors and I begin by talking out our ideas, arguments, and rebuttals. Once we have a first draft, my coauthor reads it aloud. The back-and-forth of the spoken word not only intensifies the exchange of ideas but also enhances the use of language: It is easier to spot clunkers by hearing them than by seeing them on a page. (In fact, I now recommend that all writers listen to their words as well as read them; you don’t have to be blind to do that.) Using this process I have collaborated with two of my sons, Hal and Josh, in three revisions of The Social Animal.

After I went blind the first book I attempted from scratch, Mistakes Were Made (but Not by Me), was written with my friend and colleague Carol Tavris. Even Carol, who is one of psychology’s most gifted writers, was surprised and delighted at how much the oral back-and-forth improved the final product. This book has a special poignancy for me, because it reflects another kind of full-circle experience: It is an homage to my close friend and mentor Leon Festinger. In 1957, under duress, I had read A Theory of Cognitive Dissonance in manuscript form, and it changed my life. Leon was a great scientist but utterly uninterested in applying his science to better the human condition. In Mistakes Were Made, we showed how dissonance theory can explain why so many people can do harmful, foolish, self-defeating, or cruel things and still sleep soundly at night. Leon would not have cared about explaining why so many prosecutors won’t accept DNA evidence showing that they put the wrong guy in prison, why some therapists justify the use of outdated methods that are harming their clients, why most scientists who accept money from industry convince themselves that they can’t possibly be influenced by it, and why so many quarreling couples (and nations) cannot see the other’s perspective. But I had always felt that dissonance theory was too powerful to leave in a laboratory, and so, in a sense, Carol and I dragged Leon, kicking and screaming, into the real world. Our book was published in 2007, exactly fifty years after the publication of A Theory of Cognitive Dissonance.

Today I realize that it is only my eyesight I have lost, not my vision. The first person to teach me this valuable lesson was my granddaughter Ruth, who was six years old in 2003, when my eyesight was almost completely gone. Although she is uncommonly bright, she was having difficulty learning how to read. She could not get the hang of it, and as the end of the school year approached, her teacher indicated that if she couldn’t read, she would have to repeat the first grade. How could I help her grasp the essentials of reading, when I myself was nearly blind? The obvious hook was storytelling. Ruth was always begging me to tell her stories, stories I made up as I went along, so that I almost never told the same story more than once. The next time she asked for one, I suggested that we compose it together. She was excited by the idea. Then I said, “I have a terrible memory. As we go along, I had better write it down, so that if we are interrupted, we won’t forget where we left off.” I pulled out a stack of five-by-seven-inch cards, and as we composed, I carefully printed our words on the cards. It was hard for me to see, of course, so I needed to print in large, bold letters, only four or five words to a card. There we were, one of us not knowing how to read, the other barely able to decipher even oversized words.

Ruth asked if the story could be about me when I was a little boy, and she also insisted that she be one of the central characters. “How can you be a character in a story that happened before you were born?” I asked.

“C’mon, Grandpa, you can make something up.” She was right, of course; I was thinking linearly. And so began The Adventures of Ruthie and a Little Boy Named Grandpa. Our story was an inside-out combination of Hansel and Gretel and Jack and the Beanstalk, where the old woman and the giant from the traditional fairy tales turn out to be nice people. Little Grandpa, because he is vaguely aware of the original stories, is suspicious and hesitant, while Ruth is trusting and adventurous.

After we had filled several cards, I told Ruth that I wanted to check how we had described the old woman. “Please shuffle through the cards to look for when the old woman makes her first appearance,” I said. “Here is how you find the card with the old woman on it. The O sound in ‘old’ is a circle, so look for a word that starts with a circle.” She found it. Then, a few minutes later, I would ask her to find the card with the word “oven” on it. I said, “It starts with the same circle, but then it has a V sound after the O; the V looks like an arrowhead pointed downward.” Because we were engaged in a project that was of great interest to her, and because there was no pressure, Ruth was motivated to look for letters that previously had been meaningless and confusing. Within a few days, she was reading whole sentences. Within a month, there was no stopping her. She was reading everything in sight. Of course, she would have learned to read eventually without my help. Nonetheless, because it was such an exhilarating week for Ruthie and me, although for different reasons, I arranged for the story to be published by a vanity press, with the two of us as coauthors. That little book is a sweet reminder of one of my favorite teaching experiences.

It is not by accident that I lived near enough to my grandchildren to have developed such close relationships with them. When I reflect on my life, I see with the clarity of hindsight the intersecting strands of chance and intention that made our family as tight as it is. Our decision to move to Santa Cruz was based on the conscious reasoning that if the locale was attractive enough, our children would want to establish their own lives near us. But it was by chance that at the particular moment that Vera and I had decided to leave Texas, UCSC was looking for a professor with my combination of skills and experience. Today, so many years later, Hal, Neal, and Julie still live in or near this city with their spouses and children; Josh and his family visit at every opportunity.

Was it due to chance that we lost none of our children to the siren song of drugs and rebellion that claimed so many of their generation, or was it due to our child-rearing style, which can best be termed “vigilant laissez-faire”? Vera and I can’t be sure. We tried hard to avoid meddling in their private lives while encouraging them to talk to us about anything and everything that concerned them. Even so, they kept many of their adventures, misadventures, explorations, and heartbreaks to themselves, telling us about them only years later. For example, we informed all our kids that when the bedroom door was locked, we were not to be disturbed—unless, of course, they needed us to drive them to the emergency room. In her thirties, Julie told us, with amusement, “When I was three years old, I sat outside your bedroom door for an hour, hoping you would hear me whimpering!” More seriously, Josh recently let us know that he had been picked on for a whole year by his fourth-grade teacher. “I wish you had known about it,” he complained. Perhaps we should have been a little more vigilant and a little less laissez-faire. But all of our children somehow found their own way, forgiving us our mistakes and oversights, remaining close to us and to one another.

In adulthood, each of our children chose to do the kind of work that reflects his or her individual interest and proclivity. But their choices share an underlying belief that serving the common good is what it means to live the good life. Hal became an environmental sociologist and expert on solar energy; he is training minority teenagers, unemployed contractors, and autoworkers to become proficient in a technology that has a bright present and an even brighter future. Neal became a firefighter, a first responder in rescuing people from burning buildings, automobile accidents, and the devastation of earthquakes. Julie became an educational consultant, nurturing and evaluating innovative strategies adopted by primary and secondary schools. Joshua became a professor of social psychology. When I think of how many things come around again in our lives, I smile as I recall the Jensen episode at UCSC, years before Josh arrived as a student. Today, Josh’s innovative research on developing interventions that raise the motivation and test scores of the most disadvantaged minorities is a far more effective riposte to Jensen’s misguided ideas than I (or anyone else) could have come up with at the time.

Today I realize that it is only my eyesight I have lost, not my vision. The first person to teach me this valuable lesson was my granddaughter Ruth, who was six years old in 2003, when my eyesight was almost completely gone. Although she is uncommonly bright, she was having difficulty learning how to read. She could not get the hang of it, and as the end of the school year approached, her teacher indicated that if she couldn’t read, she would have to repeat the first grade. How could I help her grasp the essentials of reading, when I myself was nearly blind? The obvious hook was storytelling. Ruth was always begging me to tell her stories, stories I made up as I went along, so that I almost never told the same story more than once. The next time she asked for one, I suggested that we compose it together. She was excited by the idea. Then I said, “I have a terrible memory. As we go along, I had better write it down, so that if we are interrupted, we won’t forget where we left off.” I pulled out a stack of five-by-seven-inch cards, and as we composed, I carefully printed our words on the cards. It was hard for me to see, of course, so I needed to print in large, bold letters, only four or five words to a card. There we were, one of us not knowing how to read, the other barely able to decipher even oversized words.

Ruth asked if the story could be about me when I was a little boy, and she also insisted that she be one of the central characters. “How can you be a character in a story that happened before you were born?” I asked.

“C’mon, Grandpa, you can make something up.” She was right, of course; I was thinking linearly. And so began The Adventures of Ruthie and a Little Boy Named Grandpa. Our story was an inside-out combination of Hansel and Gretel and Jack and the Beanstalk, where the old woman and the giant from the traditional fairy tales turn out to be nice people. Little Grandpa, because he is vaguely aware of the original stories, is suspicious and hesitant, while Ruth is trusting and adventurous.

After we had filled several cards, I told Ruth that I wanted to check how we had described the old woman. “Please shuffle through the cards to look for when the old woman makes her first appearance,” I said. “Here is how you find the card with the old woman on it. The O sound in ‘old’ is a circle, so look for a word that starts with a circle.” She found it. Then, a few minutes later, I would ask her to find the card with the word “oven” on it. I said, “It starts with the same circle, but then it has a V sound after the O; the V looks like an arrowhead pointed downward.” Because we were engaged in a project that was of great interest to her, and because there was no pressure, Ruth was motivated to look for letters that previously had been meaningless and confusing. Within a few days, she was reading whole sentences. Within a month, there was no stopping her. She was reading everything in sight. Of course, she would have learned to read eventually without my help. Nonetheless, because it was such an exhilarating week for Ruthie and me, although for different reasons, I arranged for the story to be published by a vanity press, with the two of us as coauthors. That little book is a sweet reminder of one of my favorite teaching experiences.

It is not by accident that I lived near enough to my grandchildren to have developed such close relationships with them. When I reflect on my life, I see with the clarity of hindsight the intersecting strands of chance and intention that made our family as tight as it is. Our decision to move to Santa Cruz was based on the conscious reasoning that if the locale was attractive enough, our children would want to establish their own lives near us. But it was by chance that at the particular moment that Vera and I had decided to leave Texas, UCSC was looking for a professor with my combination of skills and experience. Today, so many years later, Hal, Neal, and Julie still live in or near this city with their spouses and children; Josh and his family visit at every opportunity.

Was it due to chance that we lost none of our children to the siren song of drugs and rebellion that claimed so many of their generation, or was it due to our child-rearing style, which can best be termed “vigilant laissez-faire”? Vera and I can’t be sure. We tried hard to avoid meddling in their private lives while encouraging them to talk to us about anything and everything that concerned them. Even so, they kept many of their adventures, misadventures, explorations, and heartbreaks to themselves, telling us about them only years later. For example, we informed all our kids that when the bedroom door was locked, we were not to be disturbed—unless, of course, they needed us to drive them to the emergency room. In her thirties, Julie told us, with amusement, “When I was three years old, I sat outside your bedroom door for an hour, hoping you would hear me whimpering!” More seriously, Josh recently let us know that he had been picked on for a whole year by his fourth-grade teacher. “I wish you had known about it,” he complained. Perhaps we should have been a little more vigilant and a little less laissez-faire. But all of our children somehow found their own way, forgiving us our mistakes and oversights, remaining close to us and to one another.

In adulthood, each of our children chose to do the kind of work that reflects his or her individual interest and proclivity. But their choices share an underlying belief that serving the common good is what it means to live the good life. Hal became an environmental sociologist and expert on solar energy; he is training minority teenagers, unemployed contractors, and autoworkers to become proficient in a technology that has a bright present and an even brighter future. Neal became a firefighter, a first responder in rescuing people from burning buildings, automobile accidents, and the devastation of earthquakes. Julie became an educational consultant, nurturing and evaluating innovative strategies adopted by primary and secondary schools. Joshua became a professor of social psychology. When I think of how many things come around again in our lives, I smile as I recall the Jensen episode at UCSC, years before Josh arrived as a student. Today, Josh’s innovative research on developing interventions that raise the motivation and test scores of the most disadvantaged minorities is a far more effective riposte to Jensen’s misguided ideas than I (or anyone else) could have come up with at the time.

A few years ago Vera and I managed to make contact with our old friend Dick Alpert. Dick had suffered a serious stroke that left him slow of speech and partially paralyzed. We met in a restaurant, he in a wheelchair and I walking hesitantly with a white cane. The waiters—perhaps out of curiosity about what an old blind guy and an old cripple had to say to each other, perhaps because they recognized Baba Ram Dass—hovered near our table, surreptitiously eavesdropping. We spoke of the many ways in which our lives had intersected, of religious belief (his) and skepticism (mine), and of his transformation from developmental psychologist to spiritual leader. Near the end of our meeting, he asked me kindly, “And you, Ellie? Are you going to end up as a social psychologist?” Without a moment’s hesitation I said, “I don’t intend to end up at all!” His face lit up, and with great effort he reached for my hand. I thought he wanted to shake it, but instead he brought my hand to his lips and kissed it.

Vera and I walked outside the restaurant and watched Dick’s driver wheel him up a ramp and into the van. He looked frail and helpless, yet he was still the same bright, charming, charismatic guy I had known for most of my life. I admired the courage with which he was dealing with the debilitating effects of his stroke. Life is a roller coaster, I thought.

A few years ago Vera and I managed to make contact with our old friend Dick Alpert. Dick had suffered a serious stroke that left him slow of speech and partially paralyzed. We met in a restaurant, he in a wheelchair and I walking hesitantly with a white cane. The waiters—perhaps out of curiosity about what an old blind guy and an old cripple had to say to each other, perhaps because they recognized Baba Ram Dass—hovered near our table, surreptitiously eavesdropping. We spoke of the many ways in which our lives had intersected, of religious belief (his) and skepticism (mine), and of his transformation from developmental psychologist to spiritual leader. Near the end of our meeting, he asked me kindly, “And you, Ellie? Are you going to end up as a social psychologist?” Without a moment’s hesitation I said, “I don’t intend to end up at all!” His face lit up, and with great effort he reached for my hand. I thought he wanted to shake it, but instead he brought my hand to his lips and kissed it.

Vera and I walked outside the restaurant and watched Dick’s driver wheel him up a ramp and into the van. He looked frail and helpless, yet he was still the same bright, charming, charismatic guy I had known for most of my life. I admired the courage with which he was dealing with the debilitating effects of his stroke. Life is a roller coaster, I thought.

When I was twelve years old, Jason took me for my first ride on the roller coaster at Revere Beach. Although I had been nagging him to take me for more than a year, as the ride started, I was plenty scared. Jason, who was a veteran of thirty-odd roller-coaster rides, assured me that I had nothing to be afraid of. As usual, he was right; it was an exhilarating experience. When it was over I asked him, “What’s your favorite part of the ride?”

“What’s your favorite part?” he asked.

“I hate when you do that!” I said.

He smiled and said, “Do what?”

“I hate when you do that, too!” I shouted.

I was so annoyed at him I decided to give him the old silent treatment. But I was so eager to discuss the experience that the silent treatment lasted about thirty-four seconds. I said, “My favorite part was right after we went flying down that steep drop and we suddenly curved up again. It was so exciting I could feel my heart go right up into my throat.”

“Yeah. I know what you mean,” he said. “That used to be my favorite part, too. But you know what? After a few rides, it dawned on me that I wasn’t enjoying the rest of the experience because I kept waiting for that part of the ride to show up. So then I played a trick on myself. I pretended that my favorite part was when we were just starting down that steep hill. But then I found myself waiting for that to occur and missing out on the enjoyment of the rest of the ride. So then I pushed it back another notch and pretended to myself that my favorite part was when we were climbing the hill . . . and then it dawned on me that it’s stupid to have a favorite part. Because it’s all the roller coaster—the ups, the downs, the climbing, the falling, the gradual turns, the sharp twists. It’s all the roller coaster.”

My brother was only fourteen when he said that. Although he may not have been fully aware of it, I can see, looking at it now, he might have been using the roller coaster as a metaphor for living.

What’s my favorite part of this roller coaster I’ve been riding for seventy-eight years? As my fourteen-year-old mentor taught me, there is no favorite part. Another way of putting it is that it is all my favorite part. All of it—the plummets of blindness and loss, as well as the exhilaration that comes from giving a compelling lecture or making an important scientific discovery, and the warmth that comes from loving and being loved by my wife, kids, grandchildren, and friends. Indeed, if I were forced to choose one favorite part, I would say right now, but I guess I could have said that anywhere along the way.

When I was twelve years old, Jason took me for my first ride on the roller coaster at Revere Beach. Although I had been nagging him to take me for more than a year, as the ride started, I was plenty scared. Jason, who was a veteran of thirty-odd roller-coaster rides, assured me that I had nothing to be afraid of. As usual, he was right; it was an exhilarating experience. When it was over I asked him, “What’s your favorite part of the ride?”

“What’s your favorite part?” he asked.

“I hate when you do that!” I said.

He smiled and said, “Do what?”

“I hate when you do that, too!” I shouted.

I was so annoyed at him I decided to give him the old silent treatment. But I was so eager to discuss the experience that the silent treatment lasted about thirty-four seconds. I said, “My favorite part was right after we went flying down that steep drop and we suddenly curved up again. It was so exciting I could feel my heart go right up into my throat.”

“Yeah. I know what you mean,” he said. “That used to be my favorite part, too. But you know what? After a few rides, it dawned on me that I wasn’t enjoying the rest of the experience because I kept waiting for that part of the ride to show up. So then I played a trick on myself. I pretended that my favorite part was when we were just starting down that steep hill. But then I found myself waiting for that to occur and missing out on the enjoyment of the rest of the ride. So then I pushed it back another notch and pretended to myself that my favorite part was when we were climbing the hill . . . and then it dawned on me that it’s stupid to have a favorite part. Because it’s all the roller coaster—the ups, the downs, the climbing, the falling, the gradual turns, the sharp twists. It’s all the roller coaster.”

My brother was only fourteen when he said that. Although he may not have been fully aware of it, I can see, looking at it now, he might have been using the roller coaster as a metaphor for living.

What’s my favorite part of this roller coaster I’ve been riding for seventy-eight years? As my fourteen-year-old mentor taught me, there is no favorite part. Another way of putting it is that it is all my favorite part. All of it—the plummets of blindness and loss, as well as the exhilaration that comes from giving a compelling lecture or making an important scientific discovery, and the warmth that comes from loving and being loved by my wife, kids, grandchildren, and friends. Indeed, if I were forced to choose one favorite part, I would say right now, but I guess I could have said that anywhere along the way.

在线阅读网免费看书:http://www.yuedU88.cOm/

在线阅读网免费看书:http://www.yuedU88.cOm/